Number 1

Fall 2006

|

Volume 24 Number 1 Fall 2006 |

|

Departments:

Campus Views | Letters

| News & Notes | Parents

| Class

Notes | Aggies Remember

| End Notes

|

An Incomplete History of |

Windowless offices in the basement of Freeborn Hall have been home to The California Aggie since the late 1960s. While equipment has changed over the years, many aspects of the newsroom remain the same—including some of the furniture and editors’ long work hours. “The best few thousand hours of my life were spent down there,” said Fitz Vo, editor in chief in 2002–03. Above, some of the paper’s 2006–07 staff— managing editor Marion Everidge (from left), science and technology editor Michael Steinwand, staff writer Justin Malvin and city editor E. Ashley Wright—carry on the tradition. Photo: Karin Higgins/UC Davis |

With more than 80 student writers, editors and other staff members crowded into The California Aggie’s offices in the basement of Freeborn Hall for an evening meeting, spring 2006 Editor in Chief Matt Jojola jumped atop an old metal desk to run through the ground rules:

Avoid plagiarism, identify your sources of information, check your facts and do not accept gifts from news sources.

Managing Editor Melissa Taddei, standing on the floor nearby, held a copy of the Aggie’s 35-page style guide high over her head. “I know some of you have never seen this before, based on what you write,” she said. “Pick one up.”

After introductions, a few words of advice from other editors (“Read bigger publications,” Arts Editor Rachael Bogert urged new writers) and a round of invitations—enter a T-shirt slogan contest, take on ASUCD officers in an annual sloshball game and consider applying to become a future editor in chief—the quarterly meeting broke up for pizza and sodas.

Like a journalistic “nut graf”—a paragraph near the top of a story that summarizes what the article is about—the spring-quarter meeting was its own microcosm of the life and times of The California Aggie, a story that goes back 91 years and is still unfolding.

Ever since a handful of agricultural students founded the paper in 1915, the Aggie has been run by a revolving staff of students who report news from campus and beyond with little or no formal training or faculty guidance. Mixing long hours, camaraderie and learn-as-you-go newspapering, students assign and write the stories, sell ads, create cartoons and other illustrations, take photos, design pages, and edit and teach each other.

“It’s a miracle that it comes out five days a week. I mean that in a good way,” said Steve Magagnini, a Sacramento Bee reporter who teaches journalism classes at UC Davis and has advised the Aggie since 2002.

The paper began as an organ of the Associated Students, but over the years became a financially independent watchdog of student government, university administrators and even city and state leaders. While today the university is legally considered its publisher, with rights to direct its content, administrators take a hands-off approach.

Aggie Alums:

|

A media board—composed of administrators, staff members, students and a professional journalist—gives occasional advice, hears grievances and hires the editor in chief each year.

But Magagnini said the Aggie is remarkable for students’ independence. “They basically answer to no one,” he said. While Magagnini reviews issues and gives editors feedback each week, he said, “I don’t tell them what to do.”

The Aggie is one of the oldest student newspapers in California and one of four daily student newspapers within the 10-campus UC system, along with UC Berkeley’s Daily Californian, UCLA’s Daily Bruin and UC Santa Barbara’s Daily Nexus.

With no journalism program at UC Davis, Aggie staffers come from all fields of study—2006–07 Editor in Chief Peter Hamilton is a genetics major, as was past editor Jojola, who graduated in June.

Yet the Aggie has been one of UC Davis’ most enduring features—older than all but a handful of buildings and many of the trees—and a central part of campus life for generations of students, faculty, staff and other readers, whether they loved it or derided it as the “Raggie.”

Over the years, the paper has grown from a weekly letterpress publication produced by about a dozen students at a printing cost of about $30 an issue to a five-times-a-week, self-supporting print and online publication with a staff of more than 100 students and about $500,000 in annual advertising revenues.

The Aggie’s offices themselves, in the basement of Freeborn Hall, are their own time capsule—with the sports desk in the same spot as it was at least 15 years ago and the darkroom still in place, though unused in the digital age and renamed, after the booth in Woody Allen’s film Sleeper, the “orgasmatron.”

Former Chancellor Ted Hullar, now professor of natural resources at Cornell University, said the paper, like the Baggins End cooperative housing domes and the Aggie Band-uh, are part of UC Davis’ distinctive tradition of students shaping campus life.

Hullar, whose last years as chancellor coincided with budget cuts and student fee increases in the early 1990s, was occasionally the focus of negative stories, but he said, “I always appreciated the coverage."

![]()

1915

The University Farm was starting its eighth year, offering courses to about 300 mostly male students, when the Weekly Agricola was born Sept. 29, 1915. The paper derived its name from the campus yearbook, then the Agricola, which is Latin for farmer, though both publications would opt for more modern titles within a decade.

The fledgling newspaper was, according to a description in the 1916 yearbook, the “dream of the students and the alumni.”

In its first four-page issue, the paper introduced both itself and the school in grand terms with a front-page “Greeting”: “I am the Agricola of the University Farm School—that institution so recently sprung from the folds of time. . . . I am the voice of the institution, seeking to enlighten socially, morally and educationally. Progress is my warder; achievement is my slogan.”

Fulfilling those lofty goals apparently proved harder than anticipated. Founding Editor Casper Zwierlein lasted just three issues, though Assistant Editor William Duffy stepped up to “save the day,” according to a two-part series that ran in the paper Nov. 17 and Dec. 1, 1916, “Agricola History Full of Stirring Incidents: University Farm Weekly Publication Grows in One Year from Local to State Wide Importance.”

WantedYour favorite memories of The California Aggie to share in an upcoming issue of UC Davis Magazine. Now accepting recollections of former Aggie staffers and readers alike. Send to ucdmag@ucdavis.edu. |

According to that account, the paper was launched with the go-ahead of the Associated Students Executive Committee and plenty of how-to advice from student managers of the Daily Californian, which had been publishing at “our mother” UC Berkeley since the 1870s.

Among leading stories in the first issue of the Agricola were rules for freshman dress and behavior (including requirements that first-years wear bib overalls, tip their straw hats to upperclassmen and keep the swimming tank clean); a list of short courses open to farmers; and the return of American football, which had been banned after a number of player deaths nationwide and replaced for several years by rugby.

While quaint by modern standards, the paper mirrored newspaper styles of the times and claimed a surprisingly broad circulation. Two-thirds of its 1,200 copies went to off-campus readers statewide, according to its 1916 account. It aimed to cover both student news and topics of interest to farmers and the “country-life enthusiast.”

Novelist Jack London, a passionate farmer and advocate of scientific agriculture, was among the Agricola’s earliest readers. A letter he wrote to the editor—about his success in using Chinese methods to restore the soil at his Sonoma County ranch—appeared on the front page of the Oct. 13, 1916, issue, less than six weeks before London died at age 40.

The paper relied on advertising from the beginning, though it received subsidies from the student government for years.

In fall 1922, the Agricola called for changing the campus athletic name from the Davis Farmers to the California Aggies—“Hasn’t it a fighting twang about it?”—and soon after changed its own name, as well, to The California Aggie.

As the voice of the Associated Students, the young paper devoted much of its space to promoting participation in student events and publicizing the campus’s achievements. While it strongly advocated for student facilities, such as a gymnasium and Quad landscaping, the Aggie contained little criticism of student body leaders, faculty members or administrators in its early years.

In November 1919, a tongue-in-cheek story about a farm-management lecture apparently drew such heated reactions that the paper apologized, saying “neither discourtesy nor criticism was intended” to the professor.

But by the mid-1930s, the paper began printing letters critical of its own efforts, including complaints from unnamed critics that there were too many articles promoting the honor system and school spirit, and a call—from a club leader angrily defending a decision to move a dance from a leaky barn to the gym—for “more news, less tripe” in its coverage.

By that time, the former University Farm had grown to a UC College of Agriculture branch and the makeup of its student body was changing—with a growing number of woman students. Women had worked on the paper since the early 1920s. In fall 1935, it got its first female editor—Marie Olsson, who had been garden editor for Sunset Magazine and came to Davis from San Francisco to learn more about plants. Olsson later married fellow student and longtime UC Davis bee researcher Harry Whitcombe ’38 and helped him run a bee business; she died in Davis in August 2005.

In a November 1935 editorial, Olsson invited constructive criticism, story suggestions and broader student participation to keep the paper from falling to the “meager abilities and petty maneuverings of a small clique or partisan group,” a situation she said existed before.

![]()

1946

Beginning in the late 1930s, Aggie articles reflected a growing anxiety about the spreading war in Europe. In separate editorials, the paper urged the U.S. to seek peace through negotiation and to admit Jews fleeing Nazi persecution.

A spring 1941 reader survey found that, while most students read the paper, their favorite part was the sports page and many wanted lighter fare, like humor and gossip columns. But Pearl Harbor changed everything.

The Aggie reported a poignant campus meeting held a day after the Dec. 7, 1941, Japanese attack on U.S. battleships. With many students eager to enlist, then-Dean Knowles Ryerson urged them to stay calm; the discussion paused for a radio broadcast of President Franklin Roosevelt’s “day of infamy” speech asking Congress to declare war on Japan.

Both Ryerson and Aggie editors in following issues urged tolerance for the campus’s Japanese American students.

On Dec. 3, 1942, the Aggie reported that the campus would shut down to become an Army Signal Corps training facility. In the Jan. 28, 1943, issue, the Aggie signed off with an editorial “Until We Meet Again.”

But the Aggie was so central to the campus’ sense of community that administrators printed a special GI edition and mailed it to former students in uniform, with one headline saying, “We Attempt to Carry On.”

After the war ended and the campus reopened, the Aggie resumed publication—but with an edgier tone. With a surging enrollment that included older veterans, the paper complained about a lack of classroom buildings and other facilities and printed more pointed debate on its opinion pages.

Under Editor Max Fisher, an Army veteran and former UC Berkeley pre-med student who came to UC Davis to study farming, the paper sparked a testy exchange with an Oct. 3, 1946, editorial, “Why, Girls, Why?” complaining about female students dressed in Levis with their shirts hanging out. “Men like their women feminine and dainty.”

That prompted a letter from “Iona Dress”: “To us this business all proves what so many of the fellows seem to deny—that the girls are here at school not to captivate a man, but to get a college education and have a little fun too.”

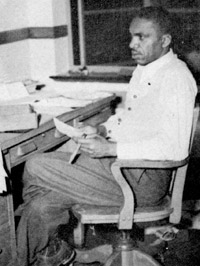

Horace Hampton, editor in 1948-49 Horace Hampton, editor in 1948-49 |

While the great majority of students at the time were white, the paper in 1948–49 got its first African American editor—Horace Hampton, a cigar-smoking Marine veteran in his 40s who, friends said, was unafraid to criticize university policies.

While the Aggie still answered to the Associated Students’ Executive Committee, editors took their own stands.

Evelyne Rowe Rominger ’51, who followed Hampton as editor in fall 1949, said she got called before the “Ex Committee” a few times over stories—one of them an editorial, “Showmanship, Hah,” criticizing students for unprofessional behavior at the campus Little International Livestock Show. Committee members thought her criticism embarrassed the campus, she said. “That day, lucky for me, Nelson Crow, editor of the Western Livestock Journal, wrote me a letter, saying it was about time someone had said something about it. I thought I was really big stuff.”

Another opinion piece drew a heated reaction from a former editor of the Davis Enterprise for including a line of praise for communist China for reducing hunger. “He said, ‘If your father wasn’t my friend, I’d blast you in my paper,’” said Rominger, who grew up near Davis and whose father graduated from UC Davis in 1913. “I thought it was kind of funny.”

With the campus growing, the Aggie went from a weekly to twice-weekly publication

in 1963.

![]()

1966

Soon after, the paper found itself confronting a variety of student organizations, as well as university administrators and the FBI, as the Free Speech Movement ignited at UC Berkeley and spread to other campuses, and students protested university restrictions on their political activities.

“Radicals . . . were bombarding us with criticism for not running enough of their ultra-liberal party line, while the many conservatives on campus were lambasting us for even covering the Free Speech Movement at all, which of course was ridiculous,” said Dan Halcomb ’66, editor in fall 1964.

“We did try to steer a middle course, however. We did try to publish all the news that seemed to fit. We published ungodly long letters to the editor and learned to develop policies for such things as we went along. But we were a true forum for the campus, and we could have filled the paper with nothing but feedback.”

While university administrators today tend to take a hands-off attitude toward the Aggie, Halcomb said he received pressure from then-Chancellor Emil Mrak to back away from covering some stories, including local protests allied with the Free Speech Movement. “I told him we had to report what happened, and he wasn’t pleased,” Halcomb said. “He never did threaten me or anything, but it was unpleasant.”

UC President Clark Kerr, however, would later thank him for an editorial that also ran in UC Berkeley’s Daily Californian and UCLA’s Daily Bruin faulting both student protest leaders and administrators for escalating tensions at a sit-in at Berkeley’s Sproul Hall that ended with student arrests. The editorial urged Kerr to talk with the students. UC regents, under pressure from then-Gov. Ronald Reagan would dismiss Kerr in 1967, largely for his perceived leniency with student protesters.

Halcomb said he ran into Kerr several years later at the Nevada County Fair in Grass Valley. “I still am awed by this—he actually remembered me by sight and by name.”

Halcomb, whose father had also been an Aggie editor before becoming a newspaper publisher, went on to work as a reporter for a variety of newspapers including the Los Angeles Times, edit a fashion magazine and run an advertising agency before “retiring” into teaching journalism at Reno High School, where he advises an award-winning student newspaper. “But the most fun I ever had was at the Cal Aggie,” Halcomb said.

In November 1966, the paper began publishing five times a week during the school year and, soon after, began asserting even greater independence.

In 1969, the Aggie broke ASUCD rules and endorsed candidates in the student body election. In a January editorial, Editor Dale Silva ’70 said: The Aggie ought to be an independent and entirely autonomous newspaper. There is no reason to be tied to an often trite and too conservative ASUCD.”

The same year, some regents began calling for campuses to exert more control over their student newspapers—saying they were too radical and profane.

At the recommendation of a blue-ribbon panel of professional journalists, UC Davis and other campuses set up boards to oversee the papers. The UC Davis media board took over from the student government the role of selecting the Aggie’s editor in chief and KDVS radio’s director.

“In the late ’60s and early ’70s, all of the UC papers started carrying gutsier stories, using some pretty crude language and pushing the liberal political agenda rather aggressively,” said John Vohs, professor emeritus of communication, who was appointed by then-Chancellor James Meyer to help create the UC Davis media board.

“A big phrase that was going around then was ‘Question Authority,’” recalled Steve Macaulay ’71, who served as a student representative on UC Davis’ first media board.

Macaulay, now an environmental consultant and director of California Urban Water Agencies, recalled board discussions over alleged bias in the Aggie and Legislative Assembly members who wanted to dictate the paper’s positions.

“I think the Aggie was at the time, and still is, a very high-quality publication,” said Macaulay. “We complained about it, too, but we counted on the Aggie to get the current news and events.”

In spring 1973, tensions rose between the Aggie and the alternative Third World News, with the Aggie accusing the minority forum of trying to gain control of the student senate and falsely printing under the Aggie’s name.

The media board voted to suspend the Aggie’s managing editor, Gary Hector, for one week, prompting accusations from the paper’s staff that the board was trying to stifle the Aggie.

The following month, the Aggie printed a letter containing a racial slur, which angered African American students, led to a second week-long suspension for Hector and got opinion page editor Mike Robbins punched in the face.

The paper denied racism and apologized for its “lack of sensitivity” in printing the letter. But the apology did little to cool tensions. Robbins said he was working in the Lower Freeborn office when three African American students walked in and confronted him. “One of the guys just punched me,” said Robbins, now an antique dealer and general contractor in Carson City, Nev. “He just whacked me a few good times. I didn’t think that was right.”

The student was charged with misdemeanor battery and the media board called for the Aggie to fire Robbins, though he kept his job and the dispute eventually died down.

![]()

1977

Under Rob Pattison ’78, who was the only editor in chief to serve two consecutive years, in 1976–78, the paper sought to sell enough ads to become self-supporting.

“While officially the Aggie was sponsored by ASUCD, we thought it important to be independent,” said Pattison, who is now a San Francisco labor attorney. “These were the years just after the Watergate scandal, and the movie All the President’s Men was released in 1976, inspiring many aspiring and active news people.”

At the same time, the paper, noting low turnout for Associated Students elections, cut back on coverage of the student government—a decision that did not sit well with Associated Student leaders.

Pattison said his most trying moments came during a January 1977 controversy over whether to accept advertising from Gallo winery, which had a long-running dispute with the United Farm Workers union. Some Aggie editors wanted to refuse the ads, while Pattison and UC attorneys believed the paper was obligated to accept them. The dispute led to media board hearings.

“The worst part for me was the strain in personal relationships with colleagues and friends who had worked together over the summer and the fall quarter 1976 to make the newspaper into something much more professional.”

Since the paper’s early years, editors had called for journalism courses, and some have been offered intermittently by faculty members, student advisers and journalists. Pattison and his successor, Rick Kushman ’79, persuaded the English department to let them teach a two-unit, pass/no pass course in news writing.

Beginning in fall 1981, the Aggie traded its manual typewriters for a computerized electronic text system—which Editor Greg Welsh said was “just like on Lou Grant,” a television series starring Ed Asner as a newspaper editor.

In December 1982, the Aggie issued results of a reader survey claiming that 77 percent of Davis residents read the Aggie, with one-third of the town reading on a daily basis, higher than local readership for the Davis Enterprise and the Sacramento Bee, findings that were challenged by the Enterprise.

In 1989, the Aggie under Business Manager Glenn Erik Millar ’89 and Editor Camille Brill ’94 experimented with once-a-week home delivery, with plans to offer subscriptions, but the proposal drew objections from the Davis Enterprise and the Davis Chamber of Commerce that the student paper would hold an unfair advantage because it pays no rent or utilities and holds tax-preferred status.

![]()

1981

|

Howard Beck ’91, editor in chief in 1990–91 and now a sportswriter covering the New York Knicks for the New York Times, said, “I always felt that we were in the crossfire of everything that happened on campus. You always felt that, if both sides were upset with you, you were probably doing OK.”

During Beck’s editorship, the state was entering a fiscal crisis and UC students faced a 40 percent hike in registration fees, the biggest increase in history. The Aggie wrote strongly worded editorials against the fee increases and tried unsuccessfully to coordinate a joint editorial with other campus papers calling for a student strike. “We wanted to shut down the system,” he said.

“We thought everything we did was the most important thing at that moment,” Beck said. “As far as we were concerned, we were No. 1 with campus news. By the end of each day, when you saw the Aggie strewn across the Quad, you think we’re all really disposable.”

Sometimes the paper’s stories have caused turmoil within its own staff. In spring 1993, when the Aggie ran an article on UC Davis’ Swords and Sandals secret society, staff members discovered that a former managing editor was a member, said Nathaniel Levine ’94, who at the time was design manager and became editor in chief a year later. “A lot of people felt kind of betrayed by that, so there was a lot of turnover.”

![]()

1994

The campus stepped in to mediate after a 1999 controversy over a cartoon. The comic strip by Jonah Ptak ’00 depicted a stray missile from Kosovo hitting Hart Hall, home to ethnic and women’s studies programs. The kicker read: “Chancellor Vanderhoef described the accident as a ‘close call.’”

The cartoon, appearing one week after Colorado’s Columbine High School shootings, sparked outrage and protests from students and faculty members, who said they felt personally threatened. Editor Sara Raley ’99 printed an apology. Chancellor Larry Vanderhoef and Provost Robert Grey chastised the paper for stepping “considerably over the line of sensitivity and respect for human rights.”

Ptak said he was widely misunderstood, that he was criticizing the administration—not attacking ethnic studies. The flap led to journalism ethics training sessions for Aggie staffers.

While the administration stepped in over that incident, it rarely does so.

Chancellor Vanderhoef meets quarterly with the paper’s editors and introduces them at the start of each school year to other campus administrators. He said he has gotten to know a number of editors, follows their careers after graduation and regularly reads Aggie columns.

“I have the highest regard for the students,” Vanderhoef said. “They’re very good, and they’re very hard-working people. Every once in a while, we have some hard interactions with the Aggie. Fortunately, those are rare events, often associated with a single person.”

The paper’s management went through an upheaval last year—with photo editor Jojola stepping into the 30- to 40-hour-a-week chief editor’s job winter quarter. The previous editor, Daniel Stone, resigned after a dispute with his editorial board over last-minute changes he made to an editorial, toning down criticism of a settlement Vanderhoef made with former Vice Chancellor for University Relations Celeste Rose.

![]()

2005

Most staff members know little about the paper’s history other than its founding date, which is listed under the front-page banner: “Serving Davis and Yolo County Since 1915.”

“When you are the editor, you wish you knew more of the history of the paper,” said 1994 editor Levine. “It’s not a well-documented history. It’s funny because the Aggie is some of the best history of the campus.”

Levine looked back through old issues for a paper for an undergraduate history course, but most Aggie editors don’t have time to go through archived copies. They are too busy putting out the latest issue.

![]()

Kathleen Holder is associate editor of UC Davis Magazine.