Volume 32 · Number 2 · Spring 2015

Pandemic busters

On the trail of the next Ebola

The UC Davis-led PREDICT program helps establish and train teams around the world to identify emerging viruses before they become pandemic.

At the height of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, the virus made a lesser-known appearance in a village thousands of miles away in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The outbreak in the Congo claimed its first life in August in a rural region in the Equateur province after a pregnant woman butchered a dead monkey found by her husband. Ebola spread to 65 other people — killing 49 of them, including the woman — before being contained in about two months.

Contrast that with the toll in West Africa, where Ebola has killed more than 10,000 people and continues to cripple Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

What made the difference? Preparedness, for sure, and the help of a UC Davis-led program.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo, where Ebola first appeared in 1976, has been working for the past five years with PREDICT, a UC Davis-managed project tasked with identifying emerging infectious diseases transmitted between humans and animals before they become a threat to human health.

PREDICT is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development as part of its Emerging Pandemic Threats program. USAID provided $75 million in 2009 to fund the first five years of the project and committed an additional $100 million last October for Phase 2, so the project can continue to identify and reduce risks from pandemic threats and build on its successes.

West Africa caught off guard

PREDICT couldn’t be everywhere though. It had identified an Ebola-susceptible region in West Africa — the region where the outbreak ultimately emerged — but had not established a team there yet due to efforts to set up in other high-risk regions.

The early stages of Ebola look similar to more prevalent West African diseases like Lassa fever and malaria. Many people were hospitalized only after they had become extremely sick — increasing their chances of infecting others. The West African outbreak started in a remote area, but spread quickly after it was introduced to more densely populated urban settings.

“They had never seen Ebola in West Africa before,” said Jonna Mazet ’90, D.V.M. ’92, M.P.V.M ’92, Ph.D. ’96, director of the UC Davis One Health Institute and PREDICT. “They weren’t ready. They had no diagnostic tests for it.”

As PREDICT embarks on its next five years, that will no longer be the case. USAID will be allocating funds to specifically address Ebola, giving the project a direct role in the region.

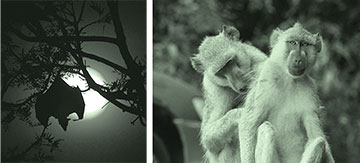

The PREDICT pandemic early warning program focuses on animal species that can carry and pass viruses to humans, like bats and monkeys living in urban areas.

Active, not reactive

Through PREDICT, the UC Davis veterinary school’s One Health Institute works with a global consortium of partners to proactively sample wildlife and test for viruses that could be passed to humans. PREDICT has dozens of scientists on its team at UC Davis, and has developed capacity in 32 laboratories overseas.

“Animals harbor many viruses that humans have not experienced in their evolutionary history,” Mazet said. “When one of those viruses spills over to us, we can be susceptible to severe disease. If the virus is also transmissible from human to human, that virus can travel around the world very quickly if left unchecked.”

PREDICT’s scientific data suggest that unknown viruses in wild mammals could total about 320,000. While a daunting number, that’s lower than many had previously believed.

“Rather than spending billions of dollars reacting to deadly outbreaks, we’re creating a system that identifies disease potential and prevents pandemics before they start,” Mazet said. “This is happening in all of the countries where PREDICT is active.”

Surveillance teams have worked in 20 countries throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, and the list of nations is expected to grow.

Researchers have collected biological samples from monkeys at temples and rodents in the urban settlements of Kathmandu, Nepal, bats in guano-mining caves in Thailand, endangered gorillas in the mountains of Uganda and Rwanda, monkeys confiscated from the illegal wildlife trade in Peru and more.

By the numbers

56,000+

nonhuman primates, bats, rodents, and other wild animals (including bushmeat samples) sampled at human-wildlife interfaces with high-risk and opportunity for viral spillover from wildlife hosts to humans.

2,500

government personnel, physicians, veterinarians, resource managers, laboratory technicians, hunters, and students trained on biosafety, surveillance, lab techniques, and disease outbreak investigation.

984

unique viruses detected in humans—815 novel viruses and 169 known viruses—the most comprehensive viral detection and discovery effort to date.

Unique expertise

When USAID sought a partner to launch a global early warning system for pandemics in 2009, it found a ready leader in Mazet, a wildlife veterinarian who specializes in disease ecology and epidemiology, the study of disease in populations.

Jonna Mazet

As director of the One Health Institute, she had experience in bringing together experts in a variety of fields as well as community members to address complex problems — among them, identifying diseases that were killing California sea otters while also putting people who eat seafood at risk. She was elected to the prestigious Institute of Medicine in 2013 for her contributions to global health.

An aspiring veterinarian from the time she was 16, Mazet planned a career in zoo medicine when she started her undergraduate studies. “Once at UC Davis, I was exposed to our rich and diverse environment and realized that I could work on wild populations and could try to save threatened populations, including our own.”

Mazet said UC Davis has a unique breadth of veterinary, human health and environmental sciences that fostered a “One Health” approach to conserving wild species by also focusing on the welfare of their human neighbors and the habitats they share

“That kind of environment, I don’t know where else in the world that exists — anywhere.”

Identifying hot spots

Traditional public health and disease surveillance systems have overlooked the link between animals, humans and the environment. PREDICT’s surveillance efforts do not.

These efforts focus on identifying “reservoir” and “spillover” species that carry and spread viruses to humans.

A reservoir is a species that can carry a virus without necessarily getting sick or dying. (Bats are believed to be a reservoir for Ebola, though the evidence is not yet conclusive.) A spillover species is one that directly interacts with humans, increasing the likelihood that it may pass on disease — monkeys that are hunted as bushmeat, for instance, as well as bats and rodents that live among people.

Kirsten Gilardi

When PREDICT started in 2009, the team compiled comprehensive data on the risks of zoonotic, or animal-to-human, diseases emerging around the world. With that data in hand, they focused on disease hot spots and identified where they would concentrate their efforts.

The work requires an understanding of a variety of geographic and sociological factors, in addition to biology.

Many human behaviors can increase the risk of disease emerging in a given location, including population growth, land-use and cultural practices.

“We know a lot about what creates a likely situation for an outbreak,” said Christine Johnson, M.P.V.M ’01, Ph.D. ’03, senior biological and ecological surveillance coordinator for PREDICT. “Our surveillance strategy is very risk-based.”

The risks vary from region to region. For example, in the three affected West African countries, bushmeat hunting is common. In others, like Uganda, it is considered taboo.

But viruses do not recognize national boundaries.

“The reality is that there are a lot of people moving across borders at all times,” said Kirsten Gilardi, D.V.M. ’93, who manages activities in Uganda and Rwanda and part of the Democratic Republic of the Congo for the PREDICT Project. “They bring their behaviors and customs with them.”

Local teams

The program is not about outsiders swooping into a country for a short period of time to sample some animals and report their findings. Once hot spots are identified, building in-country capacity to track viruses becomes the driving goal.

More than 2,500 government personnel, physicians, veterinarians, resource managers, lab technicians, hunters and students have been trained since the start of the project, creating a nimble network that can respond to threats.

“Once a country is prepared to test for one kind of virus, they’re kind of prepared for any,” Johnson said. “We work together to strengthen technical capabilities and share resources needed to do this sort of work. That way they’re prepared to recognize any virus that comes through and respond quickly.”

Practical solutions

PREDICT looks for viruses at the family level. Rather than testing specifically for Ebola, the labs test for Filovirus, the viral family to which Ebola belongs.

This family-level screening is done using consensus PCR (short for polymerase chain reaction). The molecular biology technology has been around for more than 30 years and can be done cheaply and simply — critical factors in resource-constrained regions of the world.

“We are even able to use older equipment,” said Tracey Goldstein, Ph.D. ’03, director of the One Health Institute lab at UC Davis. “In some of these countries, the equipment was just sitting around the lab unused. We’ve been able to put it to very good use with PREDICT.”

Consensus PCR allows labs to screen a large number of samples and get a sense of the diversity of viruses. From there they can decide which samples should be further examined through next-generation sequencing — a much more expensive process.

Working in remote areas also presents challenges. Many of the regions have limited refrigeration, and if samples are not properly preserved, they are of no use by the time they reach the lab.

The PREDICT team in Tanzania, for example, is equipped with a liquid nitrogen generator, which allows surveillance teams to immediately chill samples in the field.

“People from our sites around the world are sharing ideas and working together to solve problems in practical and sustainable ways,” said Woutrina Smith, D.V.M. ’01, M.P.V.M. ’01, Ph.D. ’04, Capacity Building Team lead for PREDICT.

Ready to respond

When the bush hunter’s wife fell ill in the Democratic Republic of the Congo last summer, officials initially feared that Ebola from West Africa had crossed about 3,000 miles to the heart of the continent.

A PREDICT partner lab, Institut National de Recherche Biomédicale, tested the samples and sent the genetic sequence to PREDICT teams in the United States. They identified the virus as a separate Ebola strain.

“This all happened within a week,” Goldstein said. “If PREDICT had not helped to train the lab personnel who aided in the response, that would not have been possible. The sampling and testing were done by the country’s government lab, which had viral testing protocols in place because we were able to help them do that.”

With the virus strain identified, the DRC then adapted its response plan to quickly contain the outbreak.

Similarly, Ebola outbreaks in Uganda in 2011 and 2012 were quickly contained. Uganda now has a national task force that includes ministries of health, agriculture and environment, as well as top universities — an embodiment of the One Health approach.

“We have protocols and guidelines that are immediately implemented when there’s an outbreak,” said Benard Ssebide, PREDICT country coordinator for Uganda. “We don’t have to develop a new plan every time. We just have to communicate.”

PREDICT partners

Consortium:

- USAID

- One Health Institute at UC Davis

- EcoHealth Alliance

- Metabiota

- Smithsonian Institution

- Wildlife Conservation Society

Technical partners:

- Columbia University’s Center for Infection and Immunity

- HealthMap at Boston Children’s Hospital

- The International Society for Infectious Disease

- UC San Francisco’s Viral Diagnostics and Discovery Center

- Ministries of health, agriculture and environment, universities and nonprofit organizations in 31 countries