Volume 30 · Number 1 · Fall 2012

The uncertain fate of higher education

California’s continuing crisis in higher education funding is a defining issue in this fall’s elections, the outcome of which will chart the course of college access and affordability in the Golden State for years to come.

First, the good news.

Nathan Brostrom,

UC’s executive vice president for business operations, describes the UC as a “powerful engine of opportunity, social mobility and economic development.” (Gregory Urquiaga/UC Davis)

Steve Boilard, new

director of the Center for California Studies: “Any rethinking of UC’s budget … needs to be considered in the broader context of the state’s higher education policies.” (Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Student Yena Bae, vice president of the Associated Students of UC Davis, says the financial crunch is hitting students hard. “ The UC…cannot look to students to pick up the burden every time.” (Chris Gloag Photography)

The $142.6 billion state budget passed by the Legislature and signed by Gov. Jerry Brown this summer earmarks enough money to the UC for 2012–13 to avert any immediate tuition increases.

But that tuition freeze ultimately depends on California voters approving Proposition 30, a November ballot initiative that would raise funding for K-12 schools and community colleges by increasing sales taxes and rates for high income earners. And that is a big “if,” with many far-ranging consequences, including a financial domino effect on UC campuses.

The UC Board of Regents has endorsed Proposition 30, noting that if the initiative fails, UC is scheduled to receive a budget reduction of $250 million this year and lose an additional $125 million next year.

Opponents of Proposition 30 argue that the measure would raise sales and income taxes on all Californians, not just the wealthy; would harm small businesses; and would not actually provide new funding for schools.

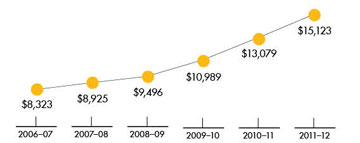

But UC President Mark Yudof has said Proposition 30’s failure would result in the UC regents implementing higher student fees in January, perhaps by as much as 20 percent (about $2,400) — another in a series of steep tuition hikes that, along with deep budget cuts, have led to angry campus protests in the past few years. (See Student fees: up and away chart).

There is a breaking point

“If students are required to pay more, the number of them that could afford a higher education will decrease dramatically,” said Yena Bae, a third-year student majoring in international relations and communication, and vice president of the Associated Students of UC Davis.

Bae said that some of her dorm mates have already left school. “The stories you hear around campus [are] disheartening as many students are forced to make a choice between ridiculous amounts of debt or to put a pause — sometimes an end — to their educations.”

On this front, Assembly Speaker John Pérez, D-Los Angeles, pushed a massive scholarship program for middle-class students, and President Barack Obama has made the interest rates on student loans a prominent piece of his re-election campaign. Indeed, the Pew Research Center reported this spring that 75 percent of people surveyed believe college is “too expensive for most Americans to afford.” In that survey, 71 percent say “it’s harder for today’s young people to pay for college than it was for their parents’ generation.”

Still, while the current fiscal crisis has resulted in state cutbacks to the UC — $750 million last year alone — student enrollment has not been reduced, said Steve Boilard, former higher education specialist for the nonpartisan California Legislative Analyst’s Office. The state has continued to fully fund Cal Grants for UC students, and the UC’s Blue and Gold financial assistance plan has helped reduce costs for some upper-middle class students.

But affordability and access are not the only issues — quality is as well. “Clearly, you can’t continually reduce funding without something having to give,” Boilard said.

Long-term consequences

Student fees: up and away

Total student fees for an undergraduate California resident attending UC Davis rose 82 percent over the past six years.(Figures include educational fee and all student services, student initiative and facilities fees. Source: UC Davis Budget and Institutional Analysis budget.ucdavis.edu)

The current financial crisis in higher education has ramifications far beyond the boundaries of our university campuses. As one of the world’s top public university systems, the UC has spurred the state’s economy, creating new jobs, businesses, ideas and inventions for decades. In fact, that was the thinking in 1862, when the federal Morrill Land Grant Act launched the creation of public universities like the UC where students from all backgrounds could receive high quality and affordable educations.

Fast forward to 1960, when the state adopted the California Master Plan for Higher Education that also made affordability and accessibility top priorities. Altogether, both visions resulted in the UC becoming a global model of higher education with direct economic benefits for the Golden State.

“In the coming year, the state will appropriate nearly $2.4 billion to the UC system, and the UC will contribute more than $46 billion in economic activity to the state,” said Nathan Brostrom, executive vice president for business operations for the 10-campus UC system. “This has to rank as one of the best investments that the state and its taxpayers can make.”

Yet the financial tsunami of 2008 and the subsequent shrinkage of California tax revenues has thrown the public funding of higher education into a tailspin.

Brostrom said state funding has declined to the same level as 1997, when there were 75,000 fewer students and one less campus in the UC.

Winder McConnell, a professor emeritus of German and former director of the Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning at UC Davis, said years of chronic underfunding is putting the quality of UC research and education at risk.

“Younger members of the faculty are already being courted by other institutions and that trend is likely to continue,” said McConnell. “Future recruitments will have to contend with a more modest package, and that further reductions may become necessary. That could eventually have a serious effect on the ability of the university to attract top-notch colleagues.”

Bae, the ASUCD vice president, said students are also losing valuable services — with funds already having been reduced for Unitrans, the Coffee House, Cross Cultural Center, Picnic Day, the Experimental College and other programs.

“With the state cutting more and the university looking for places to cut, programs and activities for students are seen as a luxury rather than a necessity,” she said.

The UC/prosperity connection

Dueling ballot measures

Rival measures on the Nov. 6 ballot—Proposition 30 by Gov. Jerry Brown and Proposition 38 by attorney Molly Munger—seek to create new revenues for education through tax increases.

It’s been 150 years since President Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into law, and yet its principles are still at work in university labs and classrooms across the country, where researchers and faculty tackle problems ranging from climate change and human rights to business ethics and engineering challenges, and where students develop the skills to succeed in the 21st century workforce.

Business sociologist Martin Kenney researches globalization’s effects on the workforce and employment, Silicon Valley and venture capital. He is concerned about what the future holds for students — especially in the area of debt — and for industries that count on UC brainpower.

In Silicon Valley, Kenney said, UC undergraduate and graduate students are highly attractive employees. But, he is quick to add, “If the budget cuts disrupt this symbiotic relationship between the UCs and the local economies, then California will have a far less promising future.”

Kenney said the state budget should reflect and foster the UC’s special role in higher education. “Our UC system has more Top 50 globally ranked universities than any nation except England. This legacy is special and fragile. It will take far-sighted politicians, university administrators, faculty and students to protect it,” Kenney said.

Rebecca Sterling, the ASUCD president, agrees.

“California’s fiscal and employment crises will only grow if the state’s decrease in funding for education continues … By educating the residents, we are making a long-term investment in the state’s economy and workforce,” said Sterling, a fourth-year student majoring in international relations and psychology.

Both she and Bae, her fellow student government leader, have traveled to the Capitol along with UC officials to advocate for more state support. “The first step is for the state and the UC to start working together,” Sterling said.

Working smarter

Rising above state cuts

Proposed by Chancellor Linda P.B. Katehi at the 2011 Fall Convocation, the 2020 Initiative is an enrollment growth plan designed to make UC Davis globally competitive beyond its current fiscal limitations (such as declining state support).

As they seek more state support for the UC, students and administrators alike point out that the system and its 10 campuses have made great strides to streamline its operations and cut costs. So planning needs to be better, smarter and more flexible than ever before.

“The best way to preserve quality, access and affordability,” Brostrom said, “is to build a multiyear financial model that recognizes the importance of state funding but also gives the university more control over its fiscal future.”

To that end, the UC — a $22 billion-a-year enterprise — is pursuing a stable, multiyear funding agreement with the state while also addressing nearly $1 billion of its funding issues by finding other revenue sources (beyond state support) and adopting an “aggressive approach” to reducing operating costs, Brostrom said.

On the latter, the UC’s Working Smarter initiative will redirect $500 million of administrative expenses to the academic mission through better procurement practices, comprehensive risk management and insurance strategies, and shared administrative enterprises. One example is a new systemwide payroll project due to start next year.

The bottom line is to educate students in a high-quality, affordable way — that is not only good for them, but for the whole of society. “Our graduates, many of whom are the first in their families to complete college, are shaping the state’s future,” said Brostrom.

A ‘broken’ Master Plan

A Capitol concern

Higher education was one of the key issues that state lawmakers grappled with this year. They considered a number of bills on the topic—among them proposed fee reductions for middle-class students, enrollment caps on students from other states and countries, and public notice requirements for student fee increases.

Boilard, who now directs the Center for California Studies, argues that California needs to revisit its Master Plan for Higher Education. Some elements of it are clearly broken, he said, and have been for some time. The “no tuition” provision, for example, has been obsolete for years.

“I’ve always felt that there’s less to the Master Plan than meets the eye,” Boilard said. “It doesn’t really say anything about what percent of the adult population should be college educated. It doesn’t really define ‘quality.’ And in any event, the Master Plan was adopted in a very different era, when the state had different education needs.”

It would make sense, he added, “to continue to embrace its broad principles — access, affordability, quality, differentiated missions — but to rethink the basic approaches we take to advance those principles.”

In a panel discussion, “A Morrill Act for the 21st Century,” in Sacramento last April, Chancellor Linda P.B. Katehi called for a national strategy for higher education. California has its master plan, but is making a big mistake by “walking away from it,” she said.

With enrollment being limited, Katehi added, “I wonder … what is going to happen to those other students who cannot enter any of the systems [UC, California State University and California Community Colleges]. Do they stay uneducated?”

Katehi was among the 152 presidents and chancellors from each of the 50 states who urged President Obama and Congress to oppose huge federal cuts to higher education due to take effect in January 2013. Those cutbacks represent “an undiscerning and blunt budget tool that would substantially harm our nation’s future” in education and scientific research, health, economic and national security, the higher education leaders wrote in a July 11 letter to President Obama.

Back at UC Davis, a new speaker series, the Provost’s Public Forums on the Public University and the Social Good, will bring experts to campus this academic year to address the issue.

In announcing the series, Ralph Hexter, the provost and executive vice chancellor, asked: “Given pressures on affordability and accessibility, will the university continue to be the engine for economic and social advancement in the future as it so clearly has been in the past?”

It is no exaggeration, Hexter said, to call this “one of the most critical moments in UC’s history.”

The provost and others believe that efforts like the speaker series can help spread the word on the holistic value of the public university to society. And time is of the essence.

If the November tax initiative fails, “it will be due to a widespread, uninformed cynicism among citizens regarding public institutions,” said Robert Huckfeldt, a professor of political science and director of the UC Center Sacramento. “If it succeeds, it will be because a compelling case has been communicated to policymakers and the public regarding the staggering consequences of continued resource declines.”

Looking toward the future, students like Bae and others worry that if UC fails to receive adequate state support, it will increasingly turn to national and international students — and the higher fees they pay — to make up the difference.

“Will my parents, as state taxpayers, not have the same opportunity to send their children to a UC campus?” she asked. “Will low-income family students like myself have the same accessibility as students who are willing to pay double to come to a UC?”

Bae said the UC and the state have to understand that increasing student tuition is not the answer: “The UC needs to think creatively in their source of funds and cannot look to students to pick up the burden every time.”

She describes higher education as an investment in “minds” — the kind that drives society forward. To take a step backward is shortsighted and dangerous.

“This is the future of California that you are putting on the line.”