Volume 28 · Number 4 · Summer 2011

Building democracy in the Middle East

Scholars analyze political unrest, push for freedom sweeping the Arab world.

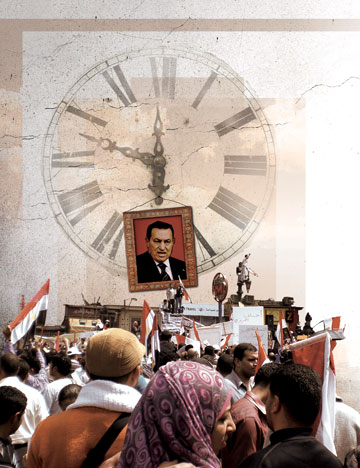

When millions of Egyptians took to Cairo's streets earlier this year to call for an end to the 30-year regime of President Hosni Mubarak, the uprising marked a transformative moment in Middle Eastern history. The revolutionary wave of protests known as the Arab Spring began in Tunisia and rippled through Egypt, Libya, Yemen, Syria, Algeria, Iran and beyond. Events are far from over, and the questions have only begun.

Photo illustration: Jay Leek/UC Davis;

Tahrir Square demonstration photo: Omnia El Shakry/UC Davis

Will this extraordinary fight for Arab liberty and dignity succeed in the long run, or will darker human impulses take control of the fragile democracy movements? UC Davis faculty experts see hopeful signs, at least in Egypt, where the democracy movement is broad-based, organizers are sophisticated in the use of social media, and protestors seem ready for meaningful — not trivial — change.

"Reform is not enough," said Omnia El Shakry, associate professor of history and a dual citizen of Egypt and the U.S., at a UC Davis teach-in in February on the Middle Eastern revolutions. "It's about removing the entire state apparatus that kept him (Mubarak) in power."

El Shakry, who visited her homeland this spring, believes Egyptians will settle only for legitimate democratic rule after living under emergency law for more than 30 years, with no free speech, no free assembly, no rule of law, no fair elections — but a lot of fear and loathing.

Egyptians, said El Shakry, want "a civil government, not a military coup, and a new constitution." Toward this, she voted in an election while in Egypt — a far more meaningful one than has taken place in recent decades.

Still, Egypt's future is uncertain, and history shows us that fledging democracies are especially vulnerable.

Witness at Tahrir Square

Noha Radwan, an assistant professor of comparative literature and Egyptian literary scholar, was in Cairo for a family emergency during the revolution. An Egyptian native and American citizen, she suffered a physical assault by pro-Mubarak thugs in Tahrir Square just minutes after finishing an interview with the U.S. television-radio program Democracy Now!

"I was saved by a soldier standing on top of a tank," Radwan said. "I yelled, 'Help!' and at first he didn't do anything." After it looked like Radwan might be killed, the soldier intervened and pulled her to safety inside the tank.

"He told me not to tell anyone" about him rescuing her. She suffered minor injuries and needed a couple of stitches to close a gash in her head.

Speaking on campus two months after Tahrir Square, Radwan described the Egyptian movement as broad — involving young and old, poor and rich alike — and not driven by Islamic radicalism or anti-Americanism.

Process of democracy

The "process of democracy," Radwan said, is the important goal in cultivating Egyptian civil society. On this, she was buoyed by a March referendum in her country that opened the way for parliamentary and presidential elections within months. Seventy-seven percent of Egyptian voters approved the constitutional amendments, but Radwan said that even those overwhelming results mattered less than the actual practice of democracy itself. Voting on substantive issues is meaningful and motivating, she explained.

To be sure, rising food prices and chronic unemployment among the young across the Middle East have greatly influenced protesters. But, the movement is also about freedom in the broadest civil sense — and that sentiment cuts across society at all levels.

"You don't need a high level of education to build democracy," she said. "We need to redistribute the wealth in the country and provide more education, medical benefits and other resources to people. The middle class shrank in recent years under the Mubarak regime."

Omnia El Shakry and Noha Radwan

(Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Women, and the power of the spoken word

Poetry and women played prominent roles in the protests in Tahrir Square in Cairo, according to Arabic and comparative literature scholar Noha Radwan

She acknowledged that, for Egypt, "it is a precarious moment, and any social movement can get hijacked" by anti-democratic groups.

Yet, the Arab world can draw on old traditions that encourage democratic, civil society, she said. From the eighth to the 10th century, the Middle East flourished with culture, learning, science, innovation and individual empowerment.

"We can build toward similar goals today," Radwan said.

The arts did play a key role in Tahrir Square, she said, illustrating that brutal, out-of-touch regimes can be brought down as much by courageous keystrokes as by bold marches through dangerous streets (see sidebar "Women, and the Power of the Spoken Word").

Bin Laden's death, rule of law

Miroslav Nincic, a political science professor and expert on U.S. foreign policy, said the death of Osama bin Laden reinforces the observation that organizations with radical agendas like Al Qadea are "less and less relevant to what people in Middle Eastern countries, especially their middle classes, care about."

The larger U.S. concerns are now promoting democracy consistently throughout the region and anticipating what the implications of the Arab Spring are for the Israeli-Palestinian relationship, he said.

One custom that helps in establishing a civil society is a "tradition of organizing for a purpose," Nincic said. Depending on the society, he said, democracies can be built from two directions — either from the "bottom up" or "top down."

"In a place like Afghanistan," Nincic said, "where the country is more decentralized and tribal, you start from the bottom and work up from the local level, where village councils and elders play key roles" in spreading support for democracy and its electoral mechanisms. That's basically the U.S. approach for Afghanistan.

Students turn out for teach-ins

"We're living in history as it unfolds," said Yena Bae, a second-year student who attended one of two faculty panel discussions in February that UC Davis held on the Middle Eastern uprisings.

"It's the job of educated college students to be aware about what is going on in the world," said Bae, who turned out to learn more about global events and issues.

Keith David Watenpaugh, a UC Davis associate professor of religious studies who studies modern Islam, human rights and peace, said the Tahrir square revolution in Egypt was an "uprising against a regime that violates human rights of its own people, day in and day out."

Several hundred people were present at the campus forums.

On the other hand, if a country has a strong national government tradition, those structures can be tailored to support democracy. "Pluralism, free speech and the rule of law are some of the most important building blocks of democracy," he added.

Either way, Nincic said, the rules of "the democratic game" and civil society must become "the accepted norm." For example, if a political party loses an election, its members must understand that this is not a call to arms — and that there will be future elections to win.

"If a group thinks otherwise, it may resort to violence and other behavior outside the norms of democracy," said Nincic, citing Yugoslavia and Iraq as two societies marked by bitter sectarian divisions.

Miroslav Nincic and David Biale

(Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

David Biale, who holds the Emanuel Ringelblum Chair in Jewish History at UC Davis, said that democratic movements can go sideways regardless of how much international support they get.

From the revolutions in Eastern Europe in 1989, and afterward, some countries (the Czech Republic, Poland) became robust democracies, but others (Russia, Belarus) became authoritarian, he said.

As for the role of the U.S. or United Nations, "It's not clear how outside forces can determine the outcome," said Biale, the winner of the 2011 UC Davis Prize for Undergraduate Teaching and Scholarly Achievement.

He noted that a new government in Egypt has great import for neighboring Israel. The Mubarak regime had engineered a "cold peace" with Israel the last couple decades following war and strife between the two countries in the 1960s and 1970s.

Biale said that a more democratically inclined Egypt will probably not be a threat to Israel. History shows that democracies are less likely to go to war against each other than are nondemocratic regimes.

Nincic agreed, noting that, "Middle East democracy movements will be good for the U.S. and allies like Israel in the long run by reducing the hatred against the U.S. as these societies are empowered to take their destinies into their own hands."

Israel, he suggested, now has a greater incentive to find a solution to the Palestinian problem. "They can only deal with so many pressing problems on all sides."

Do revolutions produce democracy?

Defining democracy

Of course, everyone wants democracy — even the most authoritarian regimes, it seems. The public relations value is obvious even if the reality is not.

"Defining democracy is one of the main challenges of political science," said Jo Andrews, associate professor of political science who is writing a book on democratization in Eastern Europe and researching the same subject in African countries. "People in different contexts define democracy in different ways."

Andrews said political scientists use tools like Polity IV to measure the degree of democracy in countries. Scores range from -10, a full autocracy, to +10, a full democracy. The other popular index is the Freedom Around the World Index published by Freedom House.

In a "full democracy," she explained, officials elected in free and fair multi-party competitive elections carry out lawmaking. To ensure this, the country must also have a free press, and there must be robust constraints on the top leader. In "partial democracies," some but not all of the characteristics of full democracies are present, Andrews said. For example, a country may hold multiparty elections, but because of free press restrictions or an absence of the rule of law, elections are not truly competitive. Some examples of partial democracies are Mexico, Russia and Venezuela. An example of an authoritarian regime is Iran.

Do revolutions lead to lasting democratic change?

One study found that, among the 88 transitions to democracy since the end of World War II, only 19 were created by revolutions. The other 69 democracies were the culmination of gradual political reform or negotiations, according to political scientists Mike Albertus of the University of Chicago and Victor Menaldo of the University of Washington.

However, the study also determined that democracies born of revolution had a higher survival rate — all 19 democracies born in revolution have lasted, while 53 of the democracies that emerged without revolt had reverted back to dictatorships.

Jo Andrews, Andy Jones and Suad Joseph

(Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Jo Andrews, a UC Davis associate professor of political science who studies political parties, democracies and electoral competition, said that economics play a critical role in whether countries make a successful transition.

"Many revolutions are the result of mass repression and of poverty and misery," Andrews said. "And, sadly, the data show that democratization in very poor countries rarely succeeds," she said.

Among the world's democracies, Andrews noted, almost all are countries in the middle or high-income groups (countries with greater than $6,000 gross domestic product per capita). "So, revolutions are no more likely to end in long-lasting democracies than gradual change."

Social media, religion

Could radical Islamists wrest control of Egypt's democracy movement and others in Tunisia, Libya and elsewhere? That happened after Iran's 1979 revolution, where the resulting theocratic regime now faces a pro-democracy movement.

Nincic and Radwan are not too worried, at least for Egypt.

"In Middle Eastern countries like Egypt," Nincic said, "the religious overlay on society is very incidental. The Egyptian people are not particularly attracted to religious fanaticism."

Radwan believes many Americans are prone to stereotypical thinking about Muslims. "While religion does play a role in Egyptian life, it is of a pious nature. Religion is more of what you do in private rather than public."

More important, scholars say, is the use of social media and the Internet, especially among the young.

"The 2011 Egyptian revolution would not have happened without social media," said Andy Jones, an English lecturer and social media expert.

He likens the Arab usage of social media to the pamphleteering of Thomas Paine during the American Revolution era, and that of French rebels who spread the philosophies of Montesquieu and Rousseau as they confronted the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI.

"Today's bloggers are the equivalent of yesterday's pamphleteers, but with the Internet as the great accelerant and amplificatory," said Jones.

Whether in Egypt or America, Jones said, today's social activists know how to make technology work for political causes. Facebook can post photographs and organize groups and meetings, Twitter can share short messages and information sources, and YouTube can paint the picture of what's happening in the street.

At the same time, Jones points out that "social media remind all of us of our responsibility to be curious and principled when gathering and sifting through all the information and wisdom available from the myriad available sources."

A bitter irony was part of the Egyptian uprising as well. As Radwan pointed out, a YouTube video depicting a case of extreme police brutality played a major role in sparking the country's "Jan. 25 Revolution" on Police Day, a national holiday commemorating Egyptian officers killed by British forces in 1952.

"Where we had only heard about these tragic episodes before, now we saw it all, shockingly so, with our own eyes," she said.

Suad Joseph, founding director of UC Davis' Middle East/South Asia Studies program, said, "One of the important lessons is that people living under those repressive regimes do want to participate politically."

Before, they were never given the chance, said Joseph, a professor of anthropology and women and gender studies. She maintains that the Western stereotype about Arab incapability to handle democracy is false and that "the enormity of this misrepresentation has ill served (U.S.) policymakers."

The fight for freedom will require "continual involvement and vigilance" on issues like free and fair elections, the rule of law and constitutional protections, she said. Democracy is hard work, and the angels — or the devils — are in the details.

"We need to trust the process," Joseph said.