Volume 24 · Number 2 · Winter 2007

News & Notes

Five out of 20 eduators at Arthur Benjamin Health Professions High School in Sacramento are UC Davis alumni, including principal Matt Perry ’87, shown above with students. Others not pictured are Barrett Drawdy ‘02, Jennifer Bilka ‘04, Allison Alair ’87 and Chris Fung ‘05. (Photo: José Luis Villegas)

A High School for Health Care

A half-dozen students dressed in medical scrubs huddled around the laboratory bench. A geneticist was demonstrating how to perform a DNA extraction from organic tissue.

They were not students in the UC Davis School of Medicine—although they may be, in perhaps 2012. The oldest among them is only 16. They are students at the Arthur A. Benjamin Health Professions High School in Sacramento.

The Sacramento City Unified School District established the school, assisted by a grant of more than $300,000 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, along with involvement of a coalition of Sacramento-area health organizations called the Healthy Community Forum. That organization’s members—which include the UC Davis Health System and other Sacramento area health care institutions—donated $300,000 toward the school’s construction. In addition, the James Irvine Foundation awarded a $200,000 grant to the school.

Health Professions High enrolled its inaugural class of ninth-graders in September 2005 in a cluster of temporary buildings on a blacktop parking lot. They attended class while construction of the school’s permanent campus was under way on an unused field adjoining an elementary school, bordered by warehouses near Interstate 5.

The new $20 million campus welcomed a second class of incoming students this past September, bringing enrollment to 275 freshmen and sophomores. UC Davis alumnus and principal Matt Perry ’87 said the school will continue admitting a new freshman class each year as existing students advance. Perry expects enrollment to reach capacity of 500 two years from now. The seven-acre campus includes 20 classrooms, science labs, a library and a multipurpose room in five buildings, arranged around a quad with a two-story clocktower.

“The school’s industry-specific focus was created in response to the increasingly critical shortage of workers in nursing, radiology, pharmacology and other medical specialties, as well as physicians to serve rural and inner-city populations,” he said. Perry, whose 24-year career encompasses science teaching and administrative posts, received a bachelor’s degree in zoology and managed the Outdoor Adventures water sports program while at UC Davis.

Claire Pomeroy, UC Davis vice chancellor for human health sciences and dean of the School of Medicine, applauds the program.

“Health Professions High will nurture and motivate talented young people to serve the patients of tomorrow. We warmly welcome its presence in our community,” Pomeroy said.

The Health Professions High curriculum emphasizes biology, chemistry and anatomy, but health-related learning is infused throughout other subject matter, including mathematics, history, geography, drama and language instruction.

Students shadow health professionals and participate in internship programs, and are assigned to produce two integrated research projects per year, working in eight-member teams. The school’s 20 teachers, five of whom are UC Davis alumni, collaboratively plan lessons for those research projects.

The school’s students voted to name the campus in honor of the late Arthur A. Benjamin, a former Sacramento high school principal. Benjamin, who served on the UC Davis Medical Center’s Community Advisory Board, championed community outreach activities that strengthened links to local health-care agencies. Earlier in his career, Benjamin managed the radiology department at the UC Davis Medical Center.

“Art Benjamin Health Professions High lets students like me experience first hand what the medical world is really like,” says Brittany Jones, a sophomore with plans of becoming a surgeon. “This school brings students closer to achieving their lifelong dream.”

For more information, visit schools.scusd.edu/healthprofessions.

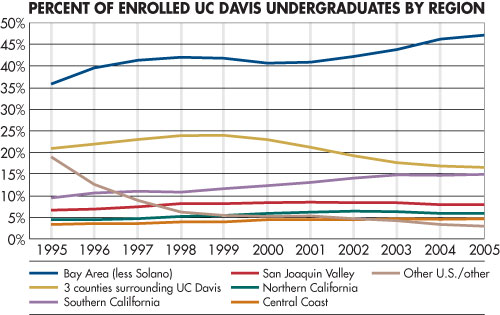

Where UC Davis Students Come From

Close to half of UC Davis students now hail from the San Francisco Bay Area, up from 36 percent a decade ago. Enrollment of students from Southern California also rose during the same period, from 10 percent to 15 percent of the total student body. Those trends partly reflect state demographics. “The college-going population base is substantially larger in those two areas than in our three local counties,” said Pamela Burnett, director of undergraduate admissions. “It could be that students in those areas are becoming increasingly aware of UC Davis.” See an interactive map showing enrollment by county.

Waste Not

Ruihong Zhang, professor of biological and agricultural engineering, shovels fresh table scraps from San Francisco Bay Area restaurants into a Biogas Energy Project digester. The project began to process eight tons of leftovers weekly in October, with a capacity to eventually handle as much as eight tons daily. If all goes well, each ton will produce enough electricity to power 10 average California homes for one day. The project is the first large-scale demonstration in the United States of the new technology developed over the past eight years by Zhang. The technology has been licensed from the university and adapted for commercial use by Onsite Power Systems Inc. Norcal Waste Systems of San Francisco is supplying the waste for the project because it already collects 300 tons of food scraps daily from 2,000 restaurants in San Francisco and 150 more in Oakland for its composting operation near Vacaville, said Chris Choate, the firm‘s vice president of sustainability.

Fighting for the Farm

In winter 1906–07, the property for the University Farm in Davis was securely in the hands of the University of California. But prospects for turning the 778 acres of farmland into a center for research and education looked anything but certain.

Plans were in the works for buildings, but there was no state funding yet to construct them. And the death of a raisin king had many Davis backers worried that the University Farm could still be moved to Fresno.

Theodore Kearney—a Fresno-area farmer described in news accounts at the time as the largest raisin grower in the nation and perhaps the world—died of heart failure aboard a steamship to England in May 1906, about seven weeks after a state commission had selected Davis for the University Farm. Kearney previously had offered 320 acres of free land for the site. His will left his 5,400-acre Fruit Vale estate to UC.

The Davis land, purchased with state funds, officially became the property of the university on Sept. 1, 1906, but that didn’t stop Fresno advocates from making their case. They made an unsuccessful appeal to the UC regents the following December, according to a report in the Davis Enterprise. Then, a Jan. 4, 1907, article in the Los Angeles Times reported that Fresno advocates were seeking state legislation to move the University Farm to the Kearney property. UC President Benjamin Wheeler said the Kearney bequest raised the possibility of establishing two UC farm schools, though he suggested that the state would be better served by beefing up agricultural instruction in high schools instead.

Ten days later, a bill was introduced in the Legislature to appropriate $132,000 to construct and equip the first buildings—including a dairy building, livestock pavilion, barns, greenhouses and a dormitory—buy livestock and farm machinery, and fund research and education at the University Farm in Davis.

The bill passed in March and construction began soon after on the first four buildings. Meanwhile, the Kearney property got tied up in court; Denis Kearney—well known as a former San Francisco labor leader who made vitriolic sandlot speeches against Chinese immigrants in the 1870s—claimed he was Theodore Kearney’s cousin and contested the will.

A judge decided in favor of UC in 1909. The university sold the Kearney property years later, but his gift did lead to the creation of a campus of sorts in Fresno County. Proceeds from the Kearney land sale were used to establish the Kearney Foundation of Soil Science to support soil, plant nutrition and water science research. The foundation, now based at UC Davis, helped buy land in the early 1960s for what is now the UC Kearney Research and Extension Center near Parlier.