Volume 25 · Number 2 · Winter 2008

Connections

Graduate Students: An Investment in Innovation

Graduate students are a crucial source of innovation and creativity for improving our world — but their financial needs are often overlooked.

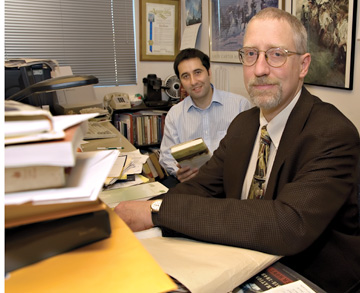

Third-year history graduate student Cristian Castro (left) and history professor Alan Taylor. Taylor believes that graduate fellowships are essential to the success of the university. (Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Reducing dependence on fossil fuels, improving biomedical imaging, writing innovative musical scores — we usually associate these accomplishments first with UC Davis professors. However, over 4,000 graduate students at UC Davis are also conducting original research and creating new works that will have social and economic benefits to our global community.

As part of the university’s Academic Vision, UC Davis plans to expand graduate education to accommodate another 2,000 students by 2015. According to dean of Graduate Studies and engineering professor Jeff Gibeling, this expansion will help nurture society’s future leaders and innovators.

It will also increase the pool of prospective high-caliber professors just in time for a wave of Baby Boomer retirements, according to statistics published by UCLA. In 2000, UCLA’s study shows, 32 percent of faculty members at the nation’s two- and four-year colleges were 55 or older. That figure was just 24 percent in 1989.

But UC Davis’ planned expansion presents a huge challenge: how to provide adequate funding to bring in the best and brightest candidates.

Gibeling says that the competition for these students can be fierce. “UC Davis must vie against some of the best-endowed universities in the nation, including both private and public institutions that are using philanthropic support to stay ahead.”

With the decline in state funding, Gibeling says, UC Davis is also looking to private support to help fulfill its mission. Fellowships are an important objective for this funding, as they are an increasingly important tool in attracting top-notch students.

“It’s a competitive market to recruit the best graduate students,” says Alan Taylor, professor of history and a Pulitzer Prize-winning scholar. “Without fellowship support, we can’t compete nationally.”

Strength Through Graduate Students

According to Taylor, since graduate students provide teaching and research assistance to professors, the quality of these students is critical to the entire academic program.

“For a number of faculty we’ve recruited, the strength of our graduate student program was the main reason they decided on UC Davis,” Taylor says.

The core of support for graduate students in the history department comes from teaching assistantships, but graduate students don’t typically jump into the classroom until their second year. Fellowships are crucial to supporting students the first year, Taylor notes, so they can ease into their second year well prepared.

Equally important are dissertation-year fellowships that enable graduate students to focus on completing their original work with fewer financial distractions. But with only 12–15 dissertation fellowships available at UC Davis, the chances of obtaining one are slim.

Taylor says his department has been fortunate over the past several years to receive endowments that provide funding for three students each year. Gifts from the late emeritus professors Paul Goodman and W. Turrentine Jackson, as well as the Reed-Smith Foundation, have contributed to the strength of the history department.

But that leaves about 13 graduate students in the history department who need support and, although the university has other fellowships available, Taylor says thousands of other graduate students across campus are vying for those limited funds.

“Potential donors understand the significance of new buildings, but it’s harder to explain the pressing importance of graduate fellowships,” Taylor says.

Converting Student Support to Biofuel

Ph.D. student Chris Simmons (left) with Jean VanderGheynst, associate professor of biological and agricultural engineering, in a lab in Bainer Hall. Simmons receives fellowship funding to support his research in converting plants to biofuel. (Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

For Chris Simmons, a third-year graduate student in biological and agricultural engineering, being awarded the prestigious Robert A. and Denzil M. Kepner Fellowship has eased financial worries and allowed him to focus more intently on his project. He is working to develop and commercialize a process to make switchgrass, or Panicum virgatum, into biofuel.

Switchgrass is high in lignocellulose, which makes it a potential plant feedstock for ethanol production, Simmons says. Certain microorganisms eat the lignocellulose during fermentation and produce ethanol. But while switchgrass is promising, making its lignocellulose suitable for fermentation is currently a major hurdle, he says. So he is collaborating with the chemical engineering and plant sciences departments to develop the technology to genetically modify switchgrass for easier conversion into bioethanol.

With the support of the $12,000 Kepner Fellowship, Simmons believes he can complete the project by late 2009 and hopes the outcome will give researchers and companies a tool to better process biofuel feedstocks into ethanol.

“It’s a long-term piece of the puzzle to ushering in widespread use of bioethanol,” Simmons says. “The results would be a big boon to people looking at this technology as a way to decrease our dependence on fossil fuels.”

Helping Students to Help Society

Ecology professor Mark Schwartz says fellowships, especially those from outside sources, traditionally have provided funding for basic science research, but not usually for applied research. This is a problem for half of the 35–40 graduate students coming into the nationally top-ranked program each year with plans to pursue careers in applied ecology, he says. These students will work for conservation organizations, environmental consulting firms, land trusts, and state and federal agencies.

“They understand their earning potential in these fields isn’t going to be tremendous, and they need to come through graduate school without much debt,” Schwartz says.

While government grants and teaching and research assistant positions provide some support to attract promising graduate students, Schwartz says these limited state and federal funds fall short.

“That’s the principal reason why we lose graduate students to other institutions — because they can offer a better package,” Schwartz says. “What we really need to work on is building a support base to help these students pursue their chosen careers.”

To find out how you can make a philanthropic gift to support graduate students at UC Davis, visit giving.ucdavis.edu or contact Jan Kingsbury at (530) 757-3083 or jkingsbury@ucdavis.edu.

Trina Wood is a Davis freelance writer.