Volume 30 · Number 2 · Winter 2013

Museum builder

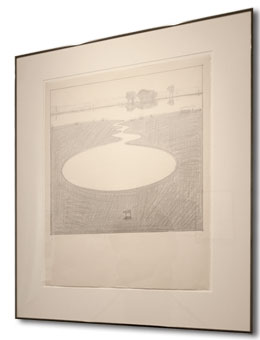

Rachel Teagle, with works from a recent Nelson Gallery exhibition: Jim Melchert’s North Atlantic, left, and Jeff Eisenberg’s Constant’s Gomorrah.

Kitty-corner to the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts, next to one of UC Davis’ large parking structures, adjacent to both a railway line and Interstate 80, is a scrubby, dusty lot. It doesn’t look particularly impressive. Nor does it look particularly close to being anything approximating a building. But during the next four years, a new art museum, the Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, will arise upon this ground. If the architectural competition being developed by Rachel Teagle, the museum’s newly appointed director, goes well, it will be a museum that not only houses top-of-the-line art but does so in a building as imaginative, and playful, as any of the world’s great, new museums—the Tate Modern in London, for example, or the Pompidou Center in Paris or, on a far smaller, lighter-hearted scale, the Museum of Jurassic Technology in Los Angeles.

So far, the signs are favorable. After all, in her two previous jobs, at museums in San Diego, Teagle presided over huge building projects. Both were critical successes.

“I want a building that captures the Tate spirit,” Teagle says, referring to the buoyant sense of possibility that lit the way for the museum’s protagonists to convert a dilapidated, out-of-commission power station on the south bank of London’s Thames river into a soaring, cavernous museum, and to then turn that space into one of the most innovative, most user-friendly museums in the world. “We can do anything here; you can let artists use it as their playground.”

She also wants a space like that of the New World Symphony, a Miami orchestral academy for up-and-coming young performers, in which the art inside permeates the grounds outside. In the orchestra’s case, they “wallcast” concerts from the New World Center into the surrounding area, creating a fluid boundary between concert hall and the world beyond. Why not, asks Teagle, create a similar fluidity around UC Davis’ new museum?

It was Teagle’s confident vision of how she would create a truly unique museum from scratch that ultimately won over the university search committee, recalls Jesse Ann Owens, dean of the Division of Humanities, Arts and Cultural Studies, who presided over the recruitment. “She was the first choice in a very competitive search. She did a spectacular interview; and had also raised $27 million in the last job she had — and has already built two capital projects. She can raise money, can build, is a very collaborative person with a huge amount of energy, and can think out of the box.”

One of her former colleagues, Hugh Davies, director of the Contemporary Art Museum in San Diego, added that Rachel and her husband, Bruce Lidl, were “great conveners,” mixing and matching eclectic crowds at barbecues they hosted at their San Diego home. She was, Davies noted, comfortable with a leadership role.

All of these are skills that Teagle will need as she seeks to turn a conception into a reality, a premier 21st century space in which to showcase the university’s strong modern and Californian collections, and its encylopedic Fine Art Collection. Despite sadness at leaving the beaches of San Diego, it’s a new chapter that Teagle, ensconced in a small office at Richard L. Nelson Hall relishes. There is, she says, a richness to campus life that ought to be a natural fit with great artistic ambitions. To tap into that richness, Teagle held a series of forums this fall with faculty, staff, students and Davis community members to explain her conception of the museum and to solicit ideas.

Robert Arneson’s The Palace at 9 a.m. from the Richard L. Nelson & The Fine Arts Collection.

One forum at the Nelson Galley drew close to 100 students — including science and engineering as well as art and design majors. Teagle encouraged participants to “say everything, no matter how crazy it is. This is the time to think really big.”

Ideas put forth at the forums for the museum site included a skate park, dog park, café, student study and art space, and an ongoing mural project to which anyone could contribute. Teagle said a neuroscientist also emailed her to ask about prospects for using the museum to study perception. Her response, she said, was “Yes, yes, yes, yes! And can we wear weird helmets?”

The museum will cost an estimated $30 million to build. Half of the constuction costs will be funded by private philanthropic gifts. Napa vinter Jan Shrem, and his wife, arts patron Maria Manetti Shrem, have given $10 million to name the museum — bringing donations to $12.1 million so far. The university will use tax-exempt bond financing for the remaining $15 million, which will be repaid from campus funds such as short-term interest earnings. No student tuition, fees or state funds will be used in building the museum.

In 2016, when the new museum opens, Teagle wants it to showcase the ideas bubbling up from all corners of the university, so as to draw in new audiences from the broader community.

“I’m a big believer in guerilla art experiences,” Teagle says. “Get out where students live and work and create provocative art experiences. That’s what we need to be shooting for.” So, too, she wants to see projection surfaces around the exterior of the museum, on which to project changing imagery; bike paths winding through art grounds; outdoor art spaces open 24 hours a day. “What is the physical analogue of the 24/7 Facebook experience? We have a real opportunity to create something special at Davis.”

“One of the things we really valued about Rachel,” Owens concluded, in explaining how Teagle emerged as the candidate of choice, “is she would understand the whole university and the region was her canvas.”

Teagle grew up in St. Louis, the daughter of two doctors — her father was a Cuban émigré who worked for the U.S. Air Force for a time, her mother a family practitioner. She was the youngest of six siblings, in an environment in which art was not an everyday part of her life. Not until she attended Washington University in St. Louis, and attended a series of talks by art history professor Angela Miller, did she realize the important role art could play in people’s lives. Miller introduced her to art from the American West. From that moment on, Teagle recalls, art became her passion.

Wayne Thiebaud's Silvan Landscape, from the Richard L. Nelson & The Fine Arts Collection.

“Nothing,” she says, laughing, “turns me on more than hanging out with artists. I love nothing more than a really provocative artist who challenges how we think, how we do business.”

Teagle, now 42, has been at the center of California’s art museum world for more than a decade, since well before she graduated from Stanford with a doctorate in art history in 2002. She was, her Stanford mentor Bryan Wolf, said, “feisty, original, brilliant, and very, very interested especially in contemporary 20th century American art.”

Since her Stanford days, she has built up a powerful set of credentials. While still a graduate student, she worked with some of the Bay Area’s more influential private collectors. Then she put in a few years at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. She was hired on as a curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego — where she spent time south of the border, cultivating contacts with young Mexican artists and putting together the materials for a widely acclaimed exhibit, Strange New World, on architecture, art and design in Tijuana.

She also presided over the building of a new downtown extension to the main museum. And most recently, beginning in 2007, she was the executive director of San Diego’s New Children’s Museum, which she stewarded through its public opening only months after accepting the job; and where she subsequently made a name for herself with a series of innovative exhibitions that called on an array of modern art talent to create experiences aimed directly at kids. It was, she proudly explains, the only museum in America to commission leading artists to create works aimed specifically at children.

On the children’s museum’s opening day, the space exhibited a large, interactive installation on dolphins, Delphine by video artist Diana Thater. Adults were bemused, Teagle remembers, but the kids “squealed with glee, making shadow puppets in the shape of mermaids.”

The young executive director also showcased images of trash by Brazilian photographer Vik Muniz — and then encouraged her young visitors to replicate Muniz’s process: arranging broken toys into patterns and photographing them.

These days, Teagle, who has lived in California for the better part of two decades, looks strikingly like a younger Susan Sarandon. When she laughs or smiles — which she does often as she talks about the world of art and of museums — her entire face is animated. The challenge of making the museum project real fills her with enthusiasm.

A new, truly 21st century museum, says Teagle, can attract new audiences, “exposing new people to contemporary art. I hope we can create a meeting place in the new museum that feels a little irreverent. It has to be casual.”

In 2005, she brought huge crowds out to San Diego’s Museum of Contemporary Art by launching a quarterly event called the Thursday Night Thing in a cavernous space just off of the old town plaza; the museum showcased music, art and film to audiences that sometimes topped 1,000 people. During her tenure at the New Children’s Museum, Teagle convinced the city’s 35 public libraries to each start lending out two museum membership cards that allow patrons to attend exhibits for free.

In 2016, Teagle will likely have similarly innovative tricks in store to bring the Davis community to her new museum. “What does it mean to be a museum of art for Davis, for Yolo County, for the greater Bay Area?” she asks. “The museum is an incredible opportunity for the university, for the city of Davis, and for me — to be able to define a museum from the ground up. There are a lot of great things about the spirit of Davis.”