Volume 31 · Number 1 · Fall 2013

The master of the art of the possible

Oncologist David Gandara is a physician on a mission—to save lung cancer patients through personalized treatment based on genetics.

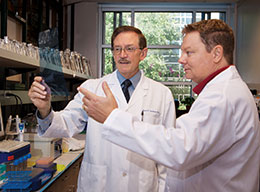

Lung cancer expert David Gandara and Philip Mack, director of molecular pharmacology, have identified differences in the tumors of smokers and nonsmokers—findings that can help in tailoring treatments for individual patients.

(José Luis Villegas photo)

Elizabeth Lacasia was in her mid-40s, recently married, healthy and athletic when she developed a stubborn cough that would not go away. A long series of doctor visits and tests finally led to an improbable diagnosis: advanced lung cancer.

Lacasia, who had a career in biotechnology and cancer drug development, sought out the leading lung cancer experts in the San Francisco Bay Area. Still, after a surgery and chemotherapy, the disease progressed. Dissatisfied with the options presented her, she kept looking. That’s when she heard about David Gandara, a leading thoracic oncologist, researcher and advocate for a revolutionary approach to the nation’s deadliest malignancy.

Gandara, senior adviser for clinical research at the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center, took a different tack. First, he ordered a battery of genetic tests. Then, based on the molecular fingerprint of Lacasia’s tumor, he put her on two drugs in a novel alternating schedule.

It’s the kind of approach Gandara uses with all of his patients — and one he anticipates that all oncologists will use in the future to determine the most precise cancer treatment.

Tailored medicine

Lung cancer, the leading cancer killer in the U.S., is classified into two primary types, according to the way the cancer cells appear under a microscope: small cell and non-small cell.

About 85 percent of lung cancers, like Lacasia’s, are non-small cell cancers. But within this group is a vast variation of malignancies with different biological properties and responses to treatment.

Gandara’s approach exploits a seeming paradox of non-small cell lung cancer: Its complexity makes it an excellent candidate for promising new “designer” or custom treatments developed to target specific genetic mutations.

For more than two decades, Gandara has conducted hundreds of trials of new drugs and combinations of drugs that can personalize lung cancer treatment for individual patients.

His research has uncovered genetic variations between lung cancer patients who smoked or never smoked, and between lung cancer patients in the U.S. and in Japan — differences that affect treatment choices and outcomes. He is venturing into the hunt for a lung cancer blood biomarker — a measureable characteristic detectable in the blood — for early diagnosis.

Gandara also has launched a collaboration with the Jackson Laboratory, a National Cancer Institute-designated research center, to take patients’ tumors and grows them in mice that do not have immune systems. The mice are then tested with new cancer agents that may be effective for those individual patients when other treatments fail.

In journal articles, international symposia and through advocacy and outreach, Gandara has sounded a steady drumbeat for a new approach to evaluating patients with lung cancer and then customizing their treatment plans.

“He is the master of the art of the possible,” says Ross Camidge, director of the thoracic oncology clinical program at the University of Colorado Hospital’s comprehensive cancer center.

Gandara’s persistence has paid off. This past spring, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer issued guidelines about which patients should be tested for molecular abnormalities, when they should undergo testing and how those tests should be administered. Gandara, the immediate past president of the lung specialists group, says: “The education of specialists is undergoing transition. There has been a lot of progress made since 2009.”

Master of collaboration

Lung cancer expert David Gandara and Philip Mack, director of molecular pharmacology, have identified differences in the tumors of smokes and nonsmokers—findings that can help in tailoring treatments for individual patients.

(José Luis Villegas photo)

Gandara didn’t foresee a career as a lung cancer specialist. He began his medical career at the Letterman Army Medical Center in San Francisco in the late 1970s focusing on breast cancer. But Gandara quickly became aware of the relative lack of expertise in lung cancer and the urgent demand for care, particularly among war veterans because of their high smoking rates.

“It was a great opportunity and a major unmet need,” he says. Hormone therapy was improving the outlook for breast cancer patients, but at that time “there was very little that could be done about advanced lung cancer.”

Gandara switched his focus. He joined the UC Davis medical faculty in 1985 and seven years later became associate director of clinical research at the UC Davis Cancer Center. He played a key role in the center’s successful quest for National Cancer Institute designation, an achievement that elevated the cancer center to the nation’s top tier in 2001.

Today, Gandara’s international reputation is based on his proven ability to organize effective research teams that include experts from diverse fields, and for working cooperatively with other cancer centers to improve lung cancer diagnostics and treatments through large-scale clinical trials.

Colorado’s Camidge said Gandara harnesses two distinct talents — an unusual ability to expertly unravel complex issues for nonexperts and a remarkable agility in steering clinicians and scientists with varied points of view in the same — though sometimes completely new — direction.

“We can have a whole bunch of very smart people from different institutions with different agendas in the same room,” Camidge says. “David uses communications skills and his ability to see the wood for the trees and gets it done.”

For Gandara, collaboration has gone hand in hand with innovation to help guide his advances. With a grant from the U.S. Department of Defense, for example, Gandara and a multidisciplinary team of scientists at UC Davis, including cancer biologist Suzanne Miyamoto, are collaborating with researchers from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas and BC Cancer Agency in Vancouver to find biomarkers in blood to identify lung cancers at their earliest stages, since early detection of the disease is a key to survival.

In addition, for 17 years, Gandara has directed a prestigious NCI NO1 grant that funds a consortium of researchers to conduct early-phase trials of genetically targeted drugs. It is one of seven such grants in the country. To get the job done, Gandara formed the California Cancer Consortium, a group consisting of researchers at UC Davis, City of Hope, University of Southern California’s cancer center, University of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania State University and the Karmano Cancer Insititute at Wayne State University.

Gandara also chairs the lung committee for the Southwest Oncology Group, (SWOG) which includes 300 sites for clinical research. One SWOG study led by Gandara broke new ground in the emerging science of pharmacogenomics, the field that tailors drug regimens to a patient’s genetic profile. The study found that a group of Japanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer survived longer — and had a higher rate of side effects — than U.S. patients with the same diagnoses when both groups were given identical therapy for the disease. A follow-up study with Primo Lara Jr., associate director for translational research at UC Davis, shed light on the differences, suggesting that subtle genetic variations can affect a person’s metabolism of chemotherapy drugs.

Similarly, Gandara and colleagues including Philip Mack, director of molecular pharmacology at UC Davis, have explored differences in the tumors of smokers and patient who had never smoked. They found that nonsmokers have fewer genetic abnormalities in their cancers, and different oncogenes (genes that, when mutated or expressed at high levels, help turn a normal cell into a cancerous one) than smokers, whose tumors often have rampant mutations. When there are fewer genetic mutations, scientists have an easier time predicting which targeted molecular therapies might work to kill the cancer cells. Those therapies include drugs that work against the most common lung cancer mutation, that of the epidermal growth factor receptor, present in 40 percent of lung cancer patients who have never smoked, and anaplastic lymphoma kinase, a gene mutation far less common in lung cancer patients.

Gandara also helped launch the cancer center’s collaboration with Jackson Laboratory, the NCI-designated research organization also known as JAX, which is based in Bar Harbor, Maine, and also has a Sacramento facility. JAX is home to thousands of mice engineered to have reduced immune systems, which makes them unique models for studying diseases and potential treatments.

Neal Goodwin is director of research and development for in vivo pharmacology services at JAX. Since starting the project with UC Davis researchers in 2010, Goodwin says, more than 1,000 patient tumors are growing in mice at JAX, representing patients from cancer centers across the country. “We have an opportunity to create mouse avatars of actual patients and to use those to research what therapies actually do to these tumors, which tumors are resistant to therapies, and how patients can overcome resistance and extend their lives,” he says.

The collaboration exemplifies translational medicine. Immediately after a patient’s tumor biopsy, tissue samples are rushed to JAX and engrafted onto mice where they can be tested for genetic abnormalities and response to different drugs. “You can only treat one patient with one regimen at a time,” Gandara explains. “But if you have 50 mice with the same patient’s tumor, you can treat it multiple different ways and also have controls. Then, you can do a genomic analysis and see what molecular pathways change in the tumor.”

Twelve hours after a mouse is given a specific treatment, scientists can biopsy the engrafted tumor to determine which pathways are turned on and off. The information allows them to extrapolate the findings to larger populations for whom a certain treatment may be effective. Use of mice speeds the pace of discovery to directly benefit patients, since a new drug can be readied for a patient when that patient’s current drug regimen fails.

These and other innovations spearheaded by Gandara have attracted the attention of Bonnie Addario, founder of the Bonnie J. Addario Lung Cancer Foundation, a leading grass-roots advocacy and research organization based in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Addario, a nine-year lung cancer survivor, points out that the lung cancer survival rate — 15 percent — hasn’t changed much in 45 years. The disease remains the leading cancer killer, and also one of the most neglected cancers in terms of research funding, in part because it is most commonly associated with smoking.

“I have one lung, one vocal cord and part of my esophagus is gone,” says Addario. “I made a promise to myself that if I survived this disease, I was going to change things. There is injustice with lung cancer. It is a disease that is stigmatized. But we are learning that anyone can get lung cancer.”

Addario enlisted Gandara in an international consortium of lung cancer thought leaders. The consortium, developed in 2008, operates a lung cancer tissue bank and partners with a genetic analysis testing company to conduct research.

In addition to Gandara’s individualized therapeutic approach based on patient and tumor genetics, Addario also liked his drive to share data to ultimately improve outcomes for all patients, regardless of their health system affiliation.

“By sharing, we not only succeed faster, but we fail faster,” Addario explains. “If you share what failed in the lab, you avoid spending month upon month and millions of dollars to get to the same place. Our goal is to make lung cancer a chronically manageable disease by 2023. With the study of the genome and working it into precision medicine, it’s possible.”

Speeding drug trials

Indeed, Gandara and his fellow oncologists are encouraged by the possibilities of genetically targeted drug therapies. At the same time, though, they share a growing frustration with the slow pace of turning new knowledge about the disease into effective, accessible treatments. He points out that only two of the last 22 late-stage trials of drugs to treat lung cancer improved survival.

Four years after receiving tailored treatment for advanced lung cancer, Elizabeth Lacasia has no detectable cancer. She credits UC Davis oncologist David Gandara and his genetics-based approach for saving her life.

(Robert Durell photo)

“If you think about both the monetary investment and also the patient resources,” Gandara says, “hundreds of millions of dollars and clinical trials enrolling many tens of thousands of patients are wasted because we have an ineffective way of developing new anti-cancer drugs.”

Teamed with the nonprofit Friends of Cancer Research in Washington, D.C., and with the support of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the Foundation of the National Institutes of Health and the National Cancer Institute, Gandara has helped develop a new paradigm to test new anti-lung cancer drugs that will be far less costly, much faster and more effective. The so-called “Master Protocol” could truly change the way cancer therapies are developed and delivered to patients. In partnership with several pharmaceutical companies, which will provide the drugs, the protocol will screen patients for various tumor biomarkers using the latest DNA sequencing technology and put them in trials for drugs most likely to be effective.

“This is really visionary,” Gandara says. “It’s saying we can’t continue to do business as usual.”

It was 10 years ago that Gandara first approached the NCI with his idea, well before researchers understood the genetics that differentiate patients and their tumors. “Now, we actually have the ability to screen a large number of patients who have cancer and figure out what the drivers for their cancer genes are,” he says.

Slated to launch in 2014, the Master Protocol project will allow oncologists to rapidly screen lung cancer patients and place them into arms of the protocol, each matching a tumor biomarker with a drug directed against it, at clinics throughout the U.S. The approach is designed to more quickly find new treatments for specific patients, even if a patient’s tumor has a rare mutation.

Until now, a drug maker might ask individual clinicians and individual centers to screen up to 1,000 patients to find just a handful who might benefit from a given drug — a difficult task for such a heterogeneous disease. With the Master Protocol, patients in clinics across the country will have their tumors screened for hundreds of different genetic abnormalities all at the same time. The information will be used to plug them into one or another arm of the project testing a specific drug to treat that particular genetic mutation.

“This Master Protocol is designed to discard drugs and targets that don’t have a major effect,” Gandara explains. “We are purposely making each of the arms of these trials smaller and hoping for a really significant effect — that is, increasing the response rate and survival. We are looking for home runs so that at the end of the day, we’re putting drugs on the market that are really effective.”

It has been nearly seven years since Elizabeth Lacasia was diagnosed with lung cancer, and four years since she has been receiving her treatment at UC Davis. Today, there is no detectable cancer, she has regained strength, is back to gardening, writing poetry, traveling and enjoying time with her husband.

“I believe,” she says without reservation, that “Dr. Gandara and the approach he took saved my life.”

In the challenging field of lung cancer, Gandara hopes that turning what is possible into hope and survival for Lacasia and others like her will be the standard of care for cancer patients everywhere.