Volume 27 · Number 2 · Winter 2010

In Print: Arnold Bauer and the Codex Cardona

When Arnold Bauer got a glimpse of an ancient Mexican illustrated book at UC Davis’ Crocker Nuclear Laboratory in 1985, he never imagined the quest that would unfold for him two decades later.

Professor emeritus Arnold Bauer (Photo by Karin Higgins, design by Jay Lee/Uc Davis)

Bauer, a scholar of Latin American history, had been invited by a colleague to look at the 427-page book, which purportedly dates to the mid-1500s and had been brought to the Crocker Lab by Stanford University anthropologists for analysis by UC Davis experts.

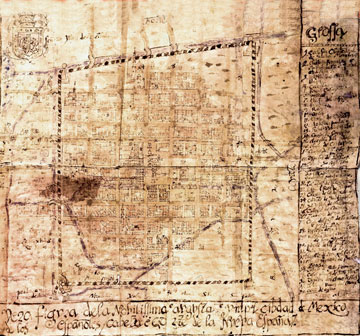

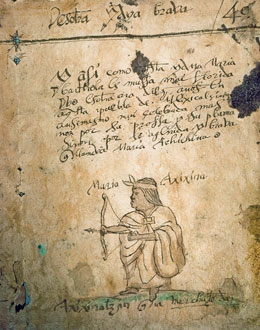

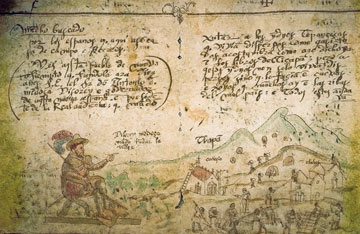

The Codex Cardona, as the book was called, was said to have been produced by native artists/scribes for Spanish officials and described Mexican history from precolonial times through Spain’s catastrophic conquest. Among its painted illustrations, in addition to scenes of everyday life, were one of conquerer Hernán Cortés at his wife’s funeral, several drawings of a Mexican woman leading an uprising against the Spanish and her subsequent hanging, and a map like no other of 16th-century Mexico City.

A rare book dealer had offered the painted manuscript to Stanford University for $6 million to $7 million. But the codex, previously unknown to scholars, had an unclear past — with no paper trail to prove a legitimate line of ownership. And questions remained about its authenticity; the tests done at the Crocker lab to determine the age of the pigments and bark paper were inconclusive. Stanford ultimately declined to buy it, and just as mysteriously as it appeared, the book disappeared again from public view.

In the following years, Bauer continued to teach history courses and pursue his own research, and spent 2000–04 directing the UC Education Abroad Center in Santiago, Chile. But he could not get the Codex Cardona out of his mind. He began reading about Mexican history and other painted books, and speculated with colleagues and anyone else who would listen about the origin and whereabouts of the Cardona. After returning to California, he began tracking the book down.

His quest would be part scholarly, part gumshoe — drawing not only on his four decades of experience in academic research, but also requiring him to locate and interview the book dealers, agents, collectors, academic experts, auction house officials and others who had touched the Codex Cardona. In the process, he learned that the artifact had been offered at various times not only to Stanford but also to Christie’s auction house in New York, Sotheby’s in London and the Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

Bauer, now a professor emeritus, chronicled his adventure in his just-released book, The Search for Cardona: On the Trail of a 16th-century Mexican Treasure (Duke University Press). He calls it a “mystery without a body.” In his search, Bauer found only the trail of the codex — and slides taken of some of the pages — but not the painted book itself. He believes the artifact is now in the possession of an antiquities dealer in Spain. He hopes his story, and a planned Spanish translation, will help save the codex from being disassembled and sold page by page to private collectors.

In this excerpt (edited for length), Bauer tells of his travels to Mexico City in January 2006 to meet a rare book dealer who told another UC Davis history professor, Andrés Reséndez, that the codex had surfaced again just a few years earlier.

— Kathleen Holder

In Search of the Codex Cardona: An excerpt

Ignacio Bernal was a cultivated, affable man of perhaps 60 with a trim gray beard and a wry, worldly manner. He also came across as a warm, gentle man. . . . I plunged right into my story, telling him how nearly 15 years ago I had come across the codex known as the Cardona when it was being offered for sale to an American university. I told him that though I was not a specialist in ancient manuscripts, I’d been poking around ever since seeing the Cardona, to try to solve some of the mystery about it and maybe even write some sort of a story.

I explained that I’d had the opportunity to talk with at least a half-dozen specialists on the subject of the Cardona, who had actually held the codex in their hands, studied it carefully, and written evaluations. Of the evaluators, three or four thought it authentic; a couple had doubts. Moreover, none of the people at the places it had been offered — and rejected — knew whether it had ever been sold or where it might be today. . . .

“Several of your clients, including young Reséndez,” I continued, still very stiffly, “told me that you have your finger on the pulse of the rare book and manuscript trade and that if I came to Mexico, it would be worth looking you up. So here I am. In fact, I’d be happy with whatever scraps of information you could give me about the Codex Cardona.”

. . . “I’m not sure it’s a very vital pulse,” he said. “Selling old books is a pretty sclerotic trade. I’d be pleased to talk with you about the Codex Cardona. I don’t know a lot; but as you can see, I happen to have several clients around this morning. It’s not common.

If you can come back in, say, half an hour?”

After he finished with his clients, Bernal told me that he had no idea where the Cardona is today. He had a few names to suggest, though, if I wanted to try to track down its story and what had become of it. . . . Though I was exhausted from my flight and short of breath because of the altitude, I felt I was finally making progress. Don Ignacio Bernal and I were hitting it off pretty well. When we sat down in the back of the store, his voice took on a more confidential tone.

ìTrue map of the very noble and imperial City of Mexico.î Not previously known publicly, this map may be the first ever made of Mexico City from on-site observation. Tests to date the Codex Cardona were inconclusiveóone suggested a post-World War II origin, though some experts believe that test reflected the age of a varnish later added to the document. Courtesy of don Guillermo GutiÈrrez Esquivel.

The recent news, he told me, leaning forward, was that the owner of the codex had kept out of sight; no one knew for sure who he was. Bernal didn’t know the full story; maybe, he said, no one did. There was still a lot of gossip floating about. But rumor had it that the owner was — or had been — Guillermo Gutiérrez Esquivel. Gutiérrez was a well-known architect and coleccionista, Bernal continued, and a big dog in the project to restore the old colonial Hospital de Betlemitas that had received substantial donations from Mexican banks and, he thought, from men like Carlos Slim, the Teléfonos de Mexico billionaire — the wealthiest man in Latin America.

Gutiérrez Esquivel himself, Bernal said, lived in a fancy house up in Lomas de Chapultepec; owned — or had owned — a house in Puerto Vallarta, and owned an old ruined plantation in the state of Morelos, the Hacienda Chiconcuac, which he was restoring on his own. He also had something to do with the Museo Franz Mayer. “A real jewel, as I’m sure you know.” Bernal also imagined that Gutiérrez Esquivel might have appropriated more than a few colonial artifacts — old ledger books, documents, other things — that his teams of excavators had found hidden away in convents and the conquistadors’ early mansions. Some of these, he believed, had ended up in the Franz Mayer, and others might have been sold to antiquarians in Mexico and elsewhere.

But then — Bernal wasn’t sure just when or how this happened — Gutiérrez Esquivel apparently got himself into hot water with an overrun of millions of dollars as part of the Centro Histórico project. Or maybe he ran off with the funds or failed to deliver. In any case, the Banco de México sued him, and as Bernal recalled, he was even jailed for a time. Bernal had the impression, but wasn’t certain, that the bank took the big house in Lomas and maybe even the Hacienda Chiconcuac.

“People say that Gutiérrez Esquivel has now changed his name,” Bernal concluded, “and has disappeared from the scene.” As for the Cardona, there was also some talk that a well-known dealer in antiquities here in Mexico City named Rodrigo Rivero Lake was somehow involved. “But I can’t get into that particular tangled tale right now” — enmarañado cuento, Bernal called it — “I’ve only heard rumors.”

The flood of new information astounded me. . . . Until now, the Cardona had moved silently, underground, among private owners and circumspect and perhaps dishonest dealers, who were understandably guarded given the doubts about provenance and about the legality of the codex’s sale abroad.

It occurred to me that Bernal, clearly fascinated by the strange saga of the Cardona, might have been inclined to embellish the story. I had seen the Hacienda Chiconcuac only a few months earlier, and people seemed to think it still belonged to “El señor Arquitecto;” I wondered if he had really changed his name.

The next evening, I was surprised by a message at the hotel from Bernal, asking if we could have a midmorning coffee at his store. He had some news for me. Eleven o’clock would be good.

Don Ignacio was waiting for me with a friendly greeting, and this time we went down the street to his favorite espresso place. He nodded hello to a handful of regular clients as we sat at a small, marble-topped table under a tin Coca-Cola umbrella.

“I’ve thought some more about your codex and talked to a couple of people last night,” he said. “It passed through a number of hands a few years ago, and most people here thought it was a falsificación, mainly because of the paper.”

I acknowledged that the same objections had been made in London and California.

María Axixina (also known as Achichina), who took part in an anti-Spanish conspiracy. Courtesy of don Guillermo Gutiérrez Esquivel.

“It wasn’t just that such an important, official document should have been on European paper at that time, three decades after the conquest,” Bernal said. “It’s that the amate [bark paper] was the wrong color. Almost all legitimate 16th-century amate documents I’ve seen are darker, a dark tan or brown. The codex we’re talking about was lighter, more like present-day amate. I can tell you that I saw the Codex Cardona in the office of an important official in Banamex — the Bank of Mexico. The man in charge of the banker’s colecciones, which are impressive, asked me, along with two specialists, or self-declared specialists, for an opinion on the codex’s authenticity.”

I’d heard this from Andrés but didn’t interrupt.

“My conclusion was ‘puede que si, puede que no,’ that the codex could be authentic and also may not be. You probably know that amate is made today.”

“I did know that,” I said. “When, more or less, did this happen, when you saw the codex?”

“Maybe some seven, eight years ago.” That would have been 1998–99.

We sipped our coffee, and Bernal took out his cell phone and called his store. In a few minutes a woman appeared with two splendid facsimiles of well-known libros de pintura. . . . Both the paper and the paint looked suitably old to my untrained eye, and the paleography looked absolutely to be authentic 16th-century script. But these documents were actually present-day copies; the frontispiece was dated 2005.

“A tlahcuilo I know made these over the past several months. They go for about $2,500 apiece. This is far from really professional-grade work; they’re made for the tourist trade. But even then you can see that the ancient art hasn’t been lost.”

As we talked, a rotund older man, jolly, with a full beard and thick glasses, strolled up to our table, greeting Bernal as if he hadn’t seen him in some time. The two talked, rather haltingly, as if Bernal wanted the man to go away. But he continued to stand there; and with some misgivings, I asked him if he’d care to join us, hoping that he wouldn’t, because I wanted the time alone with Bernal. The man sat down, however, and Bernal added another espresso to his tab. The man was an architect called Jaime Ortíz Jafous, an unusual name I didn’t get the first couple of times Bernal repeated it. “Jaime knows Gutiérrez Esquivel,” Bernal said, “and worked with him on the Franz Meyer.” Turning to Ortíz, he said, “Our friend here is interested in a curious 16th-century codex that Gutiérrez has, or at least had.” Ortíz knew Gutiérrez Esquivel fairly well; not only had he worked with him on the museum project, but he had visited Chiconcuac several times to see his collections. Ortíz’s dropping by was yet another of the fortuitous coincidences that accompanied my search for the Cardona. I thought that because of his long association, Ortíz might give me some insight into Gutiérrez Esquivel, but he didn’t offer much. . . .

The talk then turned to the Codex Cardona, which Ortíz had vaguely heard of but never seen. Ortíz was leafing through the codex facsimiles that Bernal had placed on the table, commenting on the excellent work of present-day tlahcuilos, when I said to Bernal:

“Now tell me seriously. You think the Cardona is a falsificación, but we’re talking 427 pages, 300 illustrations, a couple of spectacular maps. Would it really be possible for someone, even a team of forgers to work up something like the Cardona? Who could have done it? It’s one thing to copy a known codex” — I indicated the facsimiles — “but something else to do it from scratch. …”

“Mira,” Ortíz said, “here in Mexico we can falsify anything.”

Ortíz bid us good day and ambled up Gante, but Bernal was in no hurry to return to his store. He raised two fingers to the woman at the espresso machine, and over more coffee we continued to talk about Gutiérrez Esquivel, the reconstruction of the Centro Histórico, and possible buyers of the codex. Later, walking back to the store, he turned to a different subject, one he seemed to have kept in reserve.

“Yesterday, when you were in my store,” he said, “just a half hour after you left, a business acquaintance I hadn’t seen for several months walked in. He’s another rare book and antiquities dealer, a successful one. Over the years, he and I saw each other now and then, and I got to know him a bit. Too well, in fact; he owes me money! I remembered that he’d had something to do with the Cardona, so I mentioned your visit (not your name!). In the course of our conversation, he offhandedly mentioned that, yes, he’d been involved with the codex at Sotheby’s in London in the early ’80s (he hadn’t been sure who the owner was then) and again, six or seven years ago, in New York.”

Bernal didn’t offer his friend’s name; and when I wondered aloud about the man’s identity, he wasn’t forthcoming, so I didn’t push it. There was a pause, however, and I asked if this was the man that Bernal had referred to as the “anonymous dealer” when he talked to Andrés.

“Actually, I don’t see why I should be so guarded about his real name — he’s had more than one. The man’s name, not his original name, is Franz Friedmann Fierro. He’s Mexican-Jewish, some say a former member of the Israeli Mossad. And others might tell you that he’s one of Rivero Lake’s accomplices.”

“He’s an exotic figure,” Bernal continued, “goes around Mexico in a huge, armored todo terreno SUV with bullet-proof glass — well, lots of people do that these days — knows all the important clients for books and objets d’art, knows the Cardona, knows Gutiérrez, knows the high-end dealer Rodrigo Rivero Lake — all the main players in your story. I think he’s worked with Rivero Lake on a number of sales and consignments.”

Bernal went on to tell me a “little story” about Franz Friedmann.

“Friedmann came in one day, and we were standing in the store talking with maybe three or four clients. Suddenly there was a sharp click behind him, like a dry twig breaking — maybe someone had snapped his glasses case shut. Friedmann wheeled in a flash, looking for the weapon, front claws raised like a panther ready to spring. It was impresionante. He’s not your ordinary dealer of old books, and not the kind of man you’d want to mess with.”. . .

I returned quickly to the codex. “Did you ever learn anything more about the business in New York? I mean where the codex went or whom it was sold to after it was offered at Christie’s and rejected?”

Antonio de Mendoza, first viceroy of Mexico (1535-49), is shown directing the foundation of European-style Indian villages. Courtesy of don Guillermo Gutiérrez Esquivel.

“Well, this is my surprise for you,” Bernal said. “I asked Friedmann that question just now, this last time he was in the store. He told me directly, right to my face, that he had sold the Codex Cardona in Barcelona to a bigtime hotelero, the owner of a hotel chain. That’s all I know, and you can take it for what it’s worth. I doubt that Friedmann knows where the codex is now; moreover, the story itself may not be true.”

All fascinating, of course. Finally it seemed that several strands of my research were coming together, even if I still had only loose ends in hand. Bernal saw me wondering what to do next. “I have Friedmann’s telephone number here in Mexico, which I’ll give you, but I doubt very much that he’ll agree to meet with you or even talk with you. And if I were you” — Bernal touched his forefinger just below his right eye as if to say, be careful there! — “I’d think twice about dealing with Friedmann.”

It’s not, I gathered, that these people will break your kneecaps, but they have ways to intimidate, to discourage awkward questions. There was a lot at stake in the Cardona transaction, the questions of origin, fraud, authenticity, and illegal sale, for starters. And money: that’s what heats everything up. We talked for a few minutes more, but the subject of Friedmann and the Codex Cardona had dried up.

I said a fond farewell to don Ignacio and slowly walked west down Madero Street, past the Iturbide Palace on my left. I stopped at the entrance to the Franciscan church. This was one of the 80 Franciscan churches and convents that the order founded in Mexico during the first 30 years after the conquest, and the original part of the building here was the oldest, dating back to the early 1520s. . . .

The Codex Cardona itself may not have been compiled here (maybe parts of it were), but the friars must have seen others like it, drawn up by Nahuatl-speaking painters and scribes some 450 years ago, maybe just blocks from here in this fascinating, maddening city. Well, I thought, thinking of don Ignacio’s facsimiles, they’re still at it.

. . . . I walked the long walk back to the hotel, and the next day, reluctant to look up señor Friedman, I returned to California the second week of January, full of anticipation that I was really on the track of the codex and of its owner, whoever that might be.

Copyright Duke University Press, 2009