Volume 27 · Number 3 · Spring 2010

Degrees of Justice

Shortly after the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered the relocation of about 120,000 Japanese Americans to internment camps in the Western U.S. Nearly seven decades later, UC Davis awarded honorary degrees to 47 former Aggie students whose education was cut short.

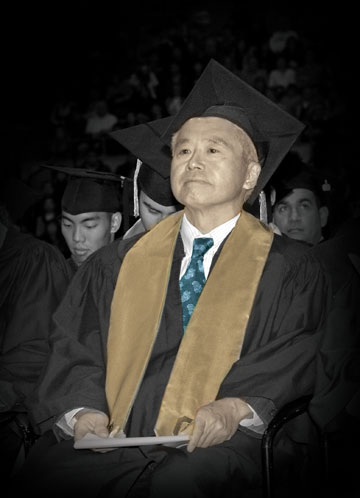

Bryan Eya

represented his father, Keiso Eya, at the December

commencement ceremony. (Photo: Cheng Saechao/UC Davis)

Kenji Tashiro will never forget the Sunday morning in early 1942 when a crestfallen UC Davis official walked into his dormitory and told him and other Japanese American students that they would soon have to leave. The U.S. government was sending them to internment camps.

“He said he knew we were responsible citizens,” Tashiro recalled, “and that this was very tragic for us and UC Davis as well.”

Tashiro’s story played out at the height of public fear on the West Coast following Japan’s Dec. 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor. In the months afterward, the U.S. government forced nearly 120,000 Japanese Americans in California, Oregon and Washington into detention centers where they would spend the next few years behind barbed wire in isolation from the rest of America.

Tashiro, who was born and raised in California, said it was “painful to be blamed unjustly.” He and his family were sent to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona.

“I knew nothing about Japan,” he said. “I considered myself a full-fledged American citizen, so it was disheartening and demoralizing.”

After one year at UC Davis, his college days were over. Like many other Japanese American students at the time, he did not return after the war to complete his studies.

But this past December, Tashiro was among 47 former Aggies to receive honorary degrees. The UC Board of Regents voted last summer to grant special degrees to more than 700 former Japanese American students systemwide, an act that UC President Mark Yudof said was “long overdue and addresses an historical tragedy.”

At the UC Davis ceremony, three former students received their degrees in person, while 10 other honorees were represented by relatives and friends. The university mailed degrees to the former students not in attendance. And for the deceased, posthumous degrees were given to their families.

Tashiro wondered if he truly deserved a degree, since he had been only a year into his studies. Still, he said he was thankful — “I am glad the UC thought about us.”

At the same time, the honorary degrees triggered memories of interment. “The camps were not quite traumatic, but it was hard,” he said.

UC protested

the internments

When the government sent Japanese Americans to the camps, many in the UC academic community objected.

Life in the camps

Tashiro said he initially found life at his detention center bleak and boring — then, spirited by youthful imagination, he made the most of it.

“At first I didn’t do much of anything, except a lot of reading,” he said. “Over time we began to organize sport activities. I remember going out of the camp to cut down large cottonwood trees so we could build a basketball post.”

He also recalled refereeing a football game played without protective pads. “A fellow broke his leg. We were playing on plain old dirt, and the clouds of dust were so bad you couldn’t tell right away what had happened.”

Tashiro had grown up on his family’s small citrus farm in northern Tulare County. When he and his family returned, they found that vandals had damaged their property — “they shot up our house” — and anti-Japanese prejudice was rampant in the small farm community.

“The people in town didn’t welcome us back at all. We had trouble for years after the war. Yes, I was most bitter about this,” said Tashiro, adding that it took almost 10 years for his family to recover and start earning money from farming again.

‘Unnecessary and illegal’

When Paul Shiozaki of Rancho Palos Verdes heard about the honorary degree he would receive 67 years after his internment, he said, “I laughed, because it was so long ago. But I’m very happy.”

Shiozaki said he had been very unhappy as a young man in the Gila River camp in Arizona, but gradually made the “adjustment.” After the war, he and his family returned to Winters to find their house and farm had been ransacked. It took years to recover, he said.

Another honoree, George Juji Omi of Santa Rosa, described the internment facilities as concentration camps and considered them “unnecessary and illegal.” Of the Japanese Americans rounded up, none was ever convicted of espionage or any other war crime.

The search for honorees

The UC regents’ vote last summer to grant the honorary degrees launched a massive search for former Japanese American students, most of whom are well into their 80s and 90s.

Omi would eventually serve in the U.S. Army, fighting in Europe.

Why would he fight for the same government that locked him up? His concept of citizenhood, he said, extends well beyond one misguided policy. “As a solider, I obey orders,” Omi said.

Susan Takahashi said that the honorary degrees given to her father, Harold Takahashi of Rocklin, and uncle,Milton Takahashi of Loomis, were “symbolic acts” of the highest magnitude.

Arlene Ikemoto Lawrence represented her uncle,

Gus Ikemoto. (Photo: Cheng Saechao/UC Davis)

“It was a period that was always very hard for them to talk about. It was a rejection. They had always felt very loyal, so this made them feel shameful,” said Takahashi, who represented the men at commencement. An administrator in the Cowell Student Health Center, she has been a UC Davis staff member for 26 years.

Now, Takahashi’s family is sharing stories and memories about a time many would rather forget.

“My dad always said he was ashamed of Japan when it bombed Pearl Harbor. He knew they had done a bad thing,” she said.

Undoing a Wrong

Many of the Japanese American students came from Central Valley farming communities to attend one of the nation’s finest agricultural institutions. Keiso Eya was at UC Davis studying plant science when he was taken away to the Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas.

He had grown up in Gardena, and the camp was “completely different” than anything he had known to that point in his life. While there was no physical mistreatment, he said, the conditions were poor and overcrowded — ”there was absolutely no privacy.”

They lived in tarpaper-covered barracks of simple frame construction without plumbing or cooking facilities of any kind.

“It was very cold in winter, as there was no insulation. And there was barbed wire all around,” Eya said.

Decades later, one might expect resentment. But Eya, who now lives in San José, dismissed that notion. “We took it in stride as much as possible. We thought it was something that couldn’t be helped.”

Eya wound up being drafted into the U.S. Army, where he trained as an intelligence officer. After the war ended, the U.S. government sent him to Tokyo to assist with the occupation effort and the rebuilding of Japanese society. In his ancestral homeland, he met his future wife and spent the next 25 years there before returning to California where, one day, his son and daughter would attend UC Davis.

“I thought Davis was a real clean town. There were too many hippies in Berkeley to send them there,” Eya joked.

When he first learned of the honorary degrees, Eya said he was both surprised and elated. “It was like walking on cloud nine. That’s a good thing about the American people — they will undo a wrong.”