Volume 29 · Number 3 · Spring 2012

Making sense of innovation

Scholars bridge the gap between campus and marketplace.

Andrew Hargadon

(Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Andrew Hargadon knows a thing or two about what it really takes to innovate.

Innovation, he says, is meaningful only when great ideas become real solutions to real issues. Hargadon, a former product designer at Apple, is now a professor of technology management and the Charles J. Soderquist Chair in Entrepreneurship at UC Davis' Graduate School of Management.

While the next great life-changing technology may already have been "invented" or dreamed up, it also may have been forgotten and left to gather dust in some corporate R&D cubicle or university science lab. The key is to identify those ideas, test and prove their value — before the dust gathers — and then connect with others who could move those ideas forward. In other words, networking counts.

Hargadon, you see, also knows a thing or two about what it really means to network.

"I worked originally in the Silicon Valley, one of those few regions where entrepreneurship thrives, and the water they swim in is rich with networks that, frankly, few of them truly appreciate," said Hargadon, author of How Breakthroughs Happen: The Surprising Truth About How Companies Innovate (Harvard Business Review Press, 2003).

At UC Davis, he is the founding director of two such promising networks — The Child Family Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship and the Energy Efficiency Center. He said each research center benefits from the bright minds on campus and the multitude of ideas they generate.

"As one of the most diverse research campuses in the world, located in one of the most vibrant economic regions in the world, UC Davis is an ideal place to host these centers," he said. "Few places offer such opportunities to pioneer new research, innovations and commercialization."

Chancellor Linda P.B. Katehi last spring issued a call for "innovation hubs" that would better connect UC Davis research with entrepreneurs, and boost the local and regional economy. One early example is the campus's decision to move several energy-related research units into offices at UC Davis West Village, the nation's largest planned zero net energy community.

In bringing those units together, the university is developing what the chancellor called a "university hub" or uHub — a prototype for the future innovation hubs.

Promoting technology

UC Davis is putting a higher value on moving ideas from the laboratory to the marketplace—with an approach that goes beyond counting patents and licenses.

And while some see the University of California as 10 individual campuses that stretch up and down the state, Hargadon sees another network for innovation, only on a much larger scale. Consider:

The UC's portfolio of active inventions increased by 5.8 percent in fiscal year 2010 to 9,883, while the number of U.S. patents owned by UC increased by 5.1 percent to 3,802. (Read more in the UC Technology Transfer Annual Report.)

As inventions and patents proliferate, they spur universities to expand technology transfer and become an even more potent force for innovation and economic development. While much work remains, there is progress to report:

Since 2005, UC Davis has helped 45 startups get off the ground. With annual research funding approaching $700 million, the university has secured more than 400 U.S. patents and earned $110 million in licensing revenue over the past 10 years.

Universities are innovation factories, Hargadon said, with the perfect mix of creativity, humanity and networking. But how does it happen? He talks about the "entrepreneurial leap:"

"Innovation requires a great idea, but also a commitment to making it happen — when the original researchers or inventors make the decision whether (and how) to take the next step."

Indeed, he is quick to add, industry and entrepreneurs could learn plenty from higher education and professors: "One of the most valuable findings of entrepreneurship research right now is how, when done effectively, it actually mimics the scientific method."

These days, the study of "innovation" is drawing more attention than ever.

'Extracting' new ideas

Mario Biagioli

Mario Biagioli is one of the world's top experts in intellectual property, science studies and patent history. He wants to know why some ideas succeed and why others fail.

Scientists — and entrepreneurs — might do well to listen to him. A former Guggenheim fellow lured away from Harvard University, Biagioli is a distinguished professor of law and science and technology studies and director of the new UC Davis Center for Science and Innovation Studies.

Like Hargadon, Biagioli agrees that universities have a high concentration of educated people and teeming ideas — virtual petri dishes for innovation.

"Extracting new ideas from smart and well educated people's brains has become a more effective way to produce value and jobs than extracting materials from the earth, which we have been doing for millennia," he said, adding that innovation could help us build a more sustainable, thoughtful world.

With that in mind, Biagioli says, scholars at the Center for Science and Innovation Studies are studying how this new economy will move forward — through new forms of collaboration among scientists and between scientists and industry; tech-transfer; emerging disciplines like nanotechnology and synthetic biology; open innovation, knowledge commons, and new patenting trends across fields and industries.

While the hard sciences have long dominated, the arts and humanities are playing increasingly vital roles in the spread of innovation. New virtual reality tools for research and teaching at the intersection of design, architecture and the sciences — like those developed at UC Davis' Humanities Innovation Lab) — are examples of an interdisciplinary spirit in innovation circles.

Indeed, Biagioli believes that the study of innovation itself requires the collaboration of several disciplines — collaborations that have rarely happened in the past: "That's the beauty and the difficulty. The academic business model of innovations studies is still very much a work in progress."

Student entrepreneurs

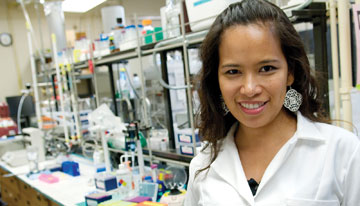

Lorna De Leoz

(T.J. Ushing/UC Davis)

Creative ventures

UC Davis students and others attending entrepreneurship academies have launched numerous commercial ventures, including:

iMobot — an exclusive license agreement to commercialize an intelligent modular robot with applications in research, education, industry, search and rescue, defense and law enforcement. Graham Ryland, M.S. '09, and Professor Harry Cheng (pictured above, left) developed the iMobot technology while Ryland was studying for his master's degree in mechanical engineering under Cheng. Ryland also attended the UC Entrepreneurship Academy.

Personalized chemotherapy — a PlatinDx assay being developed by Accelerated Medical Diagnostics to provide direct measurement of tumor responses to a microdose of platinum-based chemotherapy agents, allowing selection of the correct therapy for each patient. Founders Chong-xian Pan, M.A.S. '07, and Paul Henderson (photo above, right) are UC Davis Medical Center faculty. Henderson also attended the UC Entrepreneurship Academy.

Bioplastics — innovative technology to convert carbon found in organic wastewater to degradable and recyclable bioplastics that can be used in place of harmful petrochemical-based plastics. Micromidas incorporated in 2008 after founders and then-students John Bissell '08, Casey McGrath '08 and Kristen Matsumura '08 attended the Green Technology Entrepreneurship Academy on campus.

WicKool — a passive evaporative cooling solution that reuses condensate created by commercial rooftop HVAC units to make them more energy efficient. The technology was developed by Dick Bourne, associate director of the UC Davis Western Cooling Efficiency Center. He joined forces with Siva Gunda, Ph.D. '08, then a graduate student and business development fellow at the UC Davis Center for Entrepreneurship, to bring it into the real world.

To read more student innovation stories, visit the UC Davis Child Institute of Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

Lorna De Leoz is a student innovator. A doctoral candidate in chemistry, she researches technology to diagnose infants and children with potentially fatal diseases. In 2010, the company that she and other students launched, Pedianostics, won the "People's Choice" Prize in UC Davis' Big Bang! competition. The firm offers a platform technology to develop rapid, and more accurate, diagnostic tests to monitor diseases in children, thereby enabling better treatment.

De Leoz was inspired to take what she was doing in the lab to the market after attending the Food + Health Entrepreneurship Academy at UC Davis — put on by Hargadon's Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship.

"The academy opened my eyes to the possibilities that my research could really make a difference," said De Leoz, describing the training, mentoring and sharing of ideas there.

A mother of two, she said she was overjoyed with the chance to apply her research for the benefit of children. "I thought it was impossible, actually. There seems to be such a big gap between the lab and the market. But the entrepreneurship academy made the gap into a thin line, and I was able to step over."

Otherwise, De Leoz said, without those networks, "I would just be in my own shell."

Interdisciplinary inspiration

A university's collaborative culture is the sort of supportive environment that spurs innovation, said Steven Currall, dean and professor at the Graduate School of Management.

Currall's own research demonstrates that university scientists and engineers are more likely to produce inventions and patents if they work in an environment where management supports and encourages interdisciplinary collaboration and commercialization.

"Contrary to the stereotype of the individual innovator, our study showed evidence that the spark of innovation often happens when diverse groups of researchers are organized to collaborate across their disciplinary boundaries," said Currall, the principal investigator on the study, which defined a "productive" center or university based on its patented discoveries and inventions.

"The upshot is that, if research organizations want more innovation productivity, their leaders must use an organizational formula that emphasizes cross-boundary exchange and support for commercialization," Currall said. (Read more about his findings.)

At UC Davis, the Office of Research has launched a new program to spur interdisciplinary research teams in science, engineering, arts and the humanities with grants of up to $1 million over three years.

The aim is to provide UC Davis faculty with "seed money" to help establish projects that can compete for major funding from government, private industry, philanthropic foundations and other external sources.

Building networks

How does a university build an organization and management structure that encourages networking and innovation to flourish?

One way is through programs like the UC Entrepreneurship Academies, where researchers connect with entrepreneurs, "angel" and venture capital investors, intellectual property and corporate lawyers. Last year, the institute initiated a new program, Angels on Campus, in close collaboration with the Sacramento Angels, to provide researchers with early advice and support.

"The Sacramento Angels is the regional association of angel investors, many of whom have not only financial capital, but also great experience and broad networks — three invaluable resources for moving university research into the market," Hargadon said.

As he explains, while the growth in federal research funding over the last half-century has brought numerous scientific advances, it also created an "insular" culture for university research in how it approaches the industry marketplace. Networks and mentors help scientists overcome the hurdles in moving their ideas out of the lab and into the marketplace. UC Davis is taking steps to bridge this gap.

Researchers are not always trained in issues like intellectual property and entrepreneurship — different skill sets than required of faculty researchers — and that's where networks help, putting scientists in touch with people and firms that can manage the process of creating a product.

"All these challenges are not insurmountable," Hargadon believes. "Educating, connecting, and supporting commercialization efforts on large campuses can and does make a big difference."