Volume 25 · Number 4 · Summer 2008

News & Notes

In memoriam

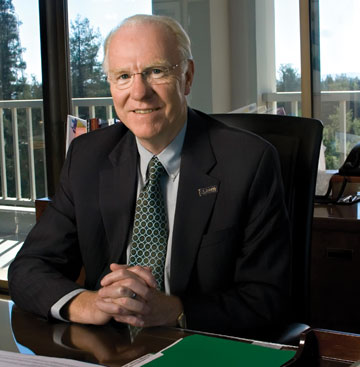

Chancellor Vanderhoef to Retire in 2009

Chancellor Larry Vanderhoef, who led UC Davis’ climb up the ranks of the nation’s finest universities while he helped open the campus’s doors to the disadvantaged and advocated academic diplomacy to help resolve global conflict, plans to step down in June 2009, at the end of the campus’s centennial year.

Vanderhoef, appointed in 1994 as UC Davis’ fifth chancellor, is one of the nation’s longest-serving university leaders. He came to the campus in 1984, first serving as executive vice chancellor and then provost/executive vice chancellor. After what will be a full quarter-century of service to UC Davis, he will take a yearlong sabbatical and then return to the faculty as a professor of plant biology. He will also continue to support the campus as chancellor emeritus.

“I can’t imagine greater good fortune than to have spent the past 24 years at UC Davis,” Vanderhoef said in a June letter to the campus community. “Along the way, there have been challenges to be sure, but together we have helped this remarkable university to reach higher, to be bolder and to achieve great distinction. For those years and those opportunities, I will always be grateful.”

The University of California system’s top leaders — UC’s current president, Robert Dynes, and incoming President Mark Yudof — led the chorus of many who praised Vanderhoef for his distinguished tenure.

Dynes pointed out that Vanderhoef “has been the senior chancellor of the UC system for several years, and all the other chancellors and I look to him for wisdom and experience.” Yudof, outgoing president of the University of Texas, said that, from afar, he has “watched the campus go from relative obscurity to the front ranks among the nation’s research universities.”

The first in his family to complete high school and one of the very few in his Wisconsin foundry town to find his way to college, Vanderhoef has dedicated his time as chancellor to removing barriers to higher education. He elevated the campus’s Division of Education to a new School of Education when other universities were downsizing theirs, expanded partnerships with community colleges, encouraged disadvantaged elementary school students to stay on track through the innovative “Reservation for College” program and partnered with leaders of regional communities of color to raise awareness of UC Davis.

On his watch, UC Davis has grown and prospered. The campus was invited in 1996 to join the prestigious Association of American Universities, representing the top 62 research universities in North America. Research funds, won competitively by UC Davis’ faculty, increased from $169 million to more than $500 million annually. The campus has risen in national rankings, too. UC Davis is now ranked eighth among all U.S. universities in contributions to society (Washington Monthly) and 11th among U.S. public universities (U.S. News & World Report). Private gifts have jumped from $40 million to nearly $200 million a year, with more than $1 billion cumulatively raised in support of programs — including $100 million from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation to launch a new School of Nursing, $35 million from Robert and Margrit Mondavi to name the Mondavi Center for the Performing Arts and the Robert Mondavi Institute for Wine and Food Science, and a $10 million gift from alumnus Maurice Gallagher to help fund a new building — Maurice J. Gallagher Jr. Hall — and endowment for the Graduate School of Management.

Under Vanderhoef’s leadership and direction, UC Davis has also made great strides in recruiting a diverse and accomplished faculty and student body. Student enrollment has grown from 22,000 to 30,000, and the faculty has increased by 44 percent. More than 4 million square feet of classroom, lab, clinical, performance and office space have been added.

But Vanderhoef’s interests and influence have stretched far beyond northern California. In 2004, for example, in the face of considerable concern and disapproval, the chancellor led what he was told was the first high-level university delegation to visit Iran since that country’s 1979 revolution.

Vanderhoef has been asked to return to Iran this November, this time as a member of a small delegation of university presidents sponsored by the Association of American Universities.

A nationwide search for a new Davis chancellor will be initiated, and a committee with regent, faculty, staff, student, alumni and foundation board representatives will advise Yudof, the incoming UC president, in the selection of Vanderhoef’s successor.

— Maril Revette Stratton

Obesity Study Flaws

Studies in mice provide the foundation for much of the belief that high-fat diets are detrimental to human health. However, the majority of studies on the health effects of high-fat diets in mice published in five respected scientific journals in 2007 were not properly designed, a survey by UC Davis researchers has found.

Out of 35 experiments, just five got it right — varying only the amounts of fat and carbohydrate in mouse diets, said Craig Warden, a professor of pediatrics and neurobiology, physiology and behavior in the Rowe Program on Genomics. The other 30 either allowed too much variation in other nutrients or gave insufficient information about mouse diets.

The articles reviewed by Warden and Janis Fisler, an associate in the nutrition department, appeared last year in the journals Cell Metabolism, Diabetes, The Journal of Clinical Investigation, Nature and Nature Medicine.

In a commentary in the April issue of Cell Metabolism, Warden and Fisler faulted studies that compare high-fat “defined” diets, often consisting of 60 percent lard, 20 percent sucrose and 20 percent casein or milk protein — the mouse equivalent of “pork rinds, ribs and Coke” — with mouse chow composed of varying amounts of carbohydrate, fat and protein.

Ingredients in each diet could throw off study results, they said.

“The bottom line is, unless the studies we do on mice are appropriately designed, we can’t use the information to give people recommendations on diet,” Warden said.

— Phyllis Brown

Picnic Prequel

As the campus nears its 2008–09 centennial celebration, we take a look back at what was happening 100 years ago.

There was no parade, no Battle of the Bands, not a single dachshund race and nary a scent of a pancake breakfast to welcome back alumni. In fact, in May 1908, not only were there no alumni, the first students had yet to set foot on the new University Farm campus. But there was a picnic.

In a sign of things to come, about a dozen people — University Farm supporters, a professor and spouses — had a picnic lunch on the campus grounds. In true fashion, the weather acted up that day with what picnicker George Pierce described in his diary as a “fearful north wind.” Still he declared the event a “pleasant gathering,” and the first official Picnic Day would follow almost exactly a year later, drawing about 2,000 people.

Sacramento Judge Peter Shields, namesake of Shields Library and author of the 1905 legislation that founded UC Davis, said in his 1954 book, The Birth of an Institution, that the elms on the south side of the Quad were “mere switches” when the campus invited the public to that first open house.

“The people looked out over the almost empty stubble field, seeking something which would suggest a prophecy of greatness,” Shields wrote. “They spread their lunches under the trees and heard speakers on a little platform tell them of what the college would be when it began to function.”

Shields, who remained a devoted UC Davis supporter all his life, would witness a dramatic transformation by the time he died at age 100 in 1962.

But even in the Farm’s earliest years, he said, the vision rapidly took shape — “turning a stubble field into a college campus and a dream into a reality.”

— Kathleen Holder

Mother-Daughter D.V.M. Duo

(Don Preisler/UC Davis photo)

Sharon Hunt Gerardo ’80, M.S. ’82, and her daughter, Angelina Gerardo, share something new in common in addition to family ties — they are both graduates of the School of Veterinary Medicine class of 2008. Sharon and Angelina said they never planned to be classmates when they each applied to veterinary programs in 2003, three years after the unexpected death of Sharon’s husband and Angelina’s father, Mike Gerardo, D.V.M. ’82. Both ended up selecting UC Davis, becoming the first parent and child to go through the veterinary school at the same time. “At first, we were a little wary about being in the same class, but soon found that it was not a problem,” Sharon said. “We requested to be placed in different lab sections so that we didn’t have all of our classes together.” And eventually, they found that they made good study partners. With June graduation came separate career paths — with Angelina heading for an Army Veterinary Corps assignment at Camp LeJeune, N.C., and Sharon, who is now remarried, planning to pursue her fourth UC Davis degree, a master’s in preventive veterinary medicine.

Namesakes: Tavernetti Bell

Thomas Tavernetti 1889ñ1934

Thomas Tavernetti was barely older than the students when he came to work for the University Farm administration in 1913, freshly graduated from UC Berkeley. The Farm was young, too, having opened just five years earlier as the first UC branch campus. As a faculty member and administrator, Tavernetti would leave a lasting mark on both the Davis campus and the growing UC system before dying of pneumonia on his 45th birthday.

He was assistant to deans and directors of the University Farm in 1913–1930 and acting director himself in 1930, as well as assistant to the dean and assistant dean of the College of Agriculture in Berkeley in 1922–34.

Claude Hutchison, campus director in 1922–24 and UC dean of agriculture in 1930–52, called Tavernetti a “very wise young man” and credited him with helping to raise the rigor of agricultural research and teaching by hiring faculty with scientific training, particularly in animal science.

“I well remember many an hour, many an afternoon, where Tom and I would sit in my office and just talk about what we needed to do to strengthen the work at Davis,” Hutchison said in an oral history interview in 1961. “I have never ceased to miss him.”

Tavernetti was the son of Italian-Swiss immigrants who ran a dairy, then grew sugar beets, lettuce and cauliflower on an 80-acre farm in the Monterey County community of Gonzales, said nephew Burton Anderson of Salinas. Tavernetti and seven of his nine siblings graduated from college, Anderson said.

One brother, James, who attended UC Davis and UC Berkeley, spent 39 years as a research engineer for UC Davis’ Department of Agricultural Engineering.

Thomas Tavernetti was well-regarded by students. A dedication in the 1919 Farm Rodeo yearbook described him as “a devoted companion of the students, a zealous and earnest worker in all endeavors in the interest of the California University Farm.”

And it was alumni, according to a 1938 report in the Los Angeles Times, who acquired the bell from Tavernetti’s demolished grammar school in Spreckels to install in his memory on campus, where it gets rung after winning football games.

— Kathleen Holder