Volume 26 · Number 2 · Winter 2009

News & Notes

PCBs: No womb for boys

Women exposed to high levels of PCBs, or polychlorinated biphenyls, are significantly less likely to give birth to baby boys, a UC Davis-led study has found.

The study provides the strongest evidence to date that maternal exposure to PCBs skews the ratio of male-to-female offspring in humans.

“These findings suggest that high maternal PCB concentrations may either favor fertilization by female sperm or result in greater male embryonic or fetal losses,” said lead study author Irva Hertz-Picciotto, an epidemiologist and professor of public health. “The association could be due to contaminants, PCB metabolites or the PCBs themselves.”

The study measured the levels of PCBs in blood taken from pregnant women during a San Francisco Bay Area study in the 1960s. The researchers then compared the PCB levels in the women’s blood with the genders of their children. It found that, for every microgram of PCBs per liter of serum, the chances of having a male child fell by 7 percent.

“The women most exposed to PCBs were 33 percent less likely to give birth to male children than the women least exposed,” Hertz-Picciotto said.

The paper was published online in Environmental Health.

PCBs are a group of man-made organic pollutants widely used in industry as cooling and insulating fluids until they were banned in the 1970s over concerns about their toxicity and accumulation in the environment. They have been associated with adverse effects on immune, reproductive, nervous and endocrine systems in people and animals.

Hertz-Picciotto said that the study will help assess the health risks of populations currently exposed to high levels of PCBs, like those that consume fish from contaminated lakes or that live near former manufacturing facilities.

Other chemicals with molecular structures similar to those of PCBs, like the flame retardants PBDEs, or polybrominated diphenyl ethers, are widely used in plastic casings of televisions, computers and other electronics, and in foam products and textiles.

— Phyllis Brown

In memoriam

Early Signs of Autism

UC Davis researchers have identified behavioral clues that could help doctors diagnose and treat autism earlier: Autistic children as young as 12 months old are more likely to spin, repetitively rotate, stare at and look out of the corners of their eyes at simple objects, including a baby bottle and a rattle.

“There is an urgent need to develop measures that can pick up early signs of autism, signs present before 24 months,” said M.I.N.D. Institute researcher Sally Ozonoff, first author of the study.

“The earlier you treat a child for autism, the more of an impact you can have on that child’s future.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics has recommended that all infants be screened for autism twice before their second birthdays. Currently, the average age of autism diagnosis in the United States is 3 years of age or older, with pediatricians looking for the hallmark social and communication signs of autism, which include language delays and lack of interest in people.

Interviews with parents, however, have shown that signs of autism often are present long before the diagnosis is made.

“The finding that the unusual use of toys is also present early in life means that this behavior could easily be added to a parent check-list or quickly assessed during a visit to a pediatrician’s office,” Ozonoff said.

In contrast to previous research that relied on the memories of parents whose children had been diagnosed with autism, this study began with a group of 12-month-olds who had not received any autism diagnosis, though some were considered high risk because they had an older sibling with autism.

Of the 66 children studied, nine were later diagnosed with autism. Seven of those nine children displayed significantly more spinning, rotating and unusual visual exploration of objects than typically developing children.

Ozonoff said follow-up research is needed before the behaviors are added to screening tests. She and her colleagues have already begun a larger five-year study.

— Phyllis Brown

First Class

As the campus celebrates its centennial, we take a look back at what was happening 100 years ago.

The first full-time students arrived at the University Farm School in January 1909, ready to learn the scientific way of farming. They were all boys, as young as 14, with a minimum of an eighth-grade education.

Some left family farms to live in the campus’s first dormitory, North Hall, and begin courses in math, English, botany, soils and dairying. But a surprising number came from towns and cities throughout California and beyond — among them sons of a lawyer, a banker, hotel keepers, a traveling salesman, a mill manager and a minister. Many of the students were first- or second-generation Californians.

Eighteen enrolled in the two- to three-year Farm School program, but another five were students from UC Berkeley and five more “special students” came from as far away as New Jersey to take subjects as suited their needs.

In newspaper articles and recruitment materials, the University of California promoted the program not just to farm youths but also to “boys who like country life or who are fond of plants and animals.” (Enrollment of girls was planned from the start but depended on construction of a second dormitory. The first girls arrived from UC Berkeley in 1914.)

One brochure touted the opportunities for students’ personal and career development, saying that “this study of nature brings out what is best in the boy and makes a better man of him. It also gives him such a knowledge of practical affairs that his earning capacity is greatly increased.”

And, indeed, those first students would go on to apply their training in a variety of ways.

Some did become lifelong farmers. Among them were Livermore wine pioneer Ernest Wente and Sacramento fruit grower Clayton Wire, who had an elementary school named for him in honor of his 30 years of service as a school board member.

Others went on to become prominent in a number of communities and fields. They included a longtime head of the Agricultural Council of California, a pharmacist, Carmel’s first car dealer, Yolo County’s chief probation officer and a UC Berkeley professor.

— Kathleen Holder

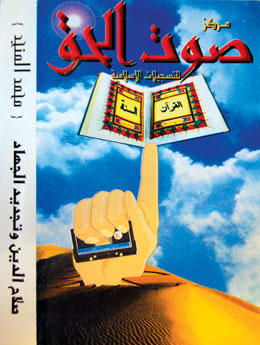

The Making of bin Laden

A cache of audiocassette tapes taken in 2001 from Osama bin Laden’s former residential compound in Qandahar, Afghanistan, is yielding new insights into the radical Islamic militant leader’s intellectual development in the years leading up to the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks.

Flagg Miller, an assistant professor of religious studies and a noted scholar of Arabic, is the first academic researcher to study the tapes.

“Bin Laden did not start out at the top of this movement. He had to earn his way there, build his credibility,” Miller said. “These cassettes help to tell us how he did that.”

The collection offers “unprecedented insight into the debates going on among bin Laden’s allies and critics in the five years leading up to the Sept. 11th attacks,” Miller said. “They also show his evolution from a relatively unpolished Muslim reformer, orator and jihad recruiter to his current persona, in which he attempts to position himself as an important intellectual and political voice on international affairs.”

The audiocassettes, along with a number of videotapes, were first acquired by a CNN producer and Afghani translator in the weeks following the Taliban’s evacuation from Qandahar on Dec. 7, 2001. After the FBI declined stewardship of the tapes, CNN turned the collection over to the Williams College Afghan Media Project, headed by anthropologist David Edwards. Edwards contacted Miller, a linguist and cultural anthropologist who studies the roles of language and poetry in contemporary Muslim reform in the Middle East. The audiocassettes are now at Yale University, where they are being cleaned, digitized and described; the process will take several years to complete.

The more than 1,500 audiocasettes, dating from the late 1960s through 2000, include sermons, political speeches, lectures, formal interviews, exchanges between students and teachers, telephone conversations, radio broadcasts, recordings of battles and Islamic anthems, as well as trivia contests and studio-recorded audio dramas. Twenty tapes contain recordings of bin Laden; 12 of these include material previously unpublished in any language, according to Miller.

For links to two bin Laden recordings, with English translations, click here.

— Claudia Morain