Volume 26 · Number 3 · Spring 2009

News & Notes

Melissa Bain, assistant professor of veterinary medicine and epidemiology, has trained her own cats at home for the past 10 years.(Karin Higgins/UC Davis)

Sit, Kitty! Stay!

Playing fetch — it’s not just for dogs anymore.

Sit, roll over, shake hands — and this coming from an animal that takes 20-hour naps? At the UC Davis Companion Animal Behavior Service, you can learn how to train your cat just like a person would train a dog.

“Some people have a notion that cats are aloof or unfriendly,” said Melissa Bain, assistant professor of veterinary medicine and epidemiology at the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, “but they’re not!” Bain, a board-certified veterinary behaviorist, has trained her own cats at home for the past 10 years. “It’s not mainstream, and most people haven’t done it, but that doesn’t mean they can’t,” Bain said.

She said in the past, she’s seen cats play fetch, roll over, get in a box and shake hands, to name a few tricks. This is opposed to the usual tricks cats perform on a daily basis — eat, sleep and shed fur. And while animal trainers in Hollywood have been training cats for decades, this is a fairly new phenomenon for the common cat.

According to Bain, it’s important to use positive reinforcement when training cats, like rewarding them with treats, instead of punishing them, which makes them much less likely to want to participate in the training process. She also uses “clicking training” to help her cat recognize what she wants him to do. “It’s not magic — the clicker is a tool, and it can’t be used as punishment unless you throw it at them,” she said.

“You’ve got to find the motivation,” Bain said, and according to her, food usually works best. She also suggests rewarding small steps so cats understand what they’re doing correctly and keeping the sessions short — only a few minutes at a time.

While the vast majority of cats seen at the Behavior Service are there for behavioral issues, Bain said she wants eventually to offer programs for cats to socialize, like a kitten kindergarten that could allow cat owners to have more fun with their pets and expose them to the outside world. “They don’t go anywhere fun,” Bain said.

She also hopes to offer classes for cats soon, but currently people can bring their cats in for individual advice. And while the cats are getting individual attention, people can take their puppies to “Yappy” Hour.

For more information, visit the Companion Animal Behavior Service site.

A Presidential Precedent

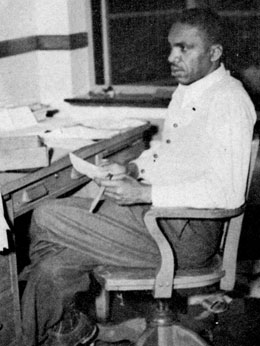

Horace Hampton became UC Davis' first African American student president in 1949.

UC Davis students led American voters by nearly six decades in electing their first African American president. Horace Hampton, a 38-year-old Marine veteran attending UC Davis on the G.I. Bill, became student body president in 1949. He was one of the first blacks to be elected to such a post at a major U.S. university and the first in the UC system (UCLA students also elected a black student body president later the same year). Like President Obama, Hampton campaigned on a call for change. In Hampton’s case, he urged that the student government be more active and conduct outreach. One of a handful of African Americans on campus, Hampton was also editor of The California Aggie student newspaper. He resigned as student body president after six months, however, finding that it took too much time from his studies. He graduated in 1950 with a degree in agricultural education, and later headed the Fresno West Development Corp. and the Yosemite Capital Investment Co., organizations that fostered African American businesses. Hampton died in 1991.

Centennial: Picnic Day Debuts

As the campus celebrates its centennial, we take a look back at what was happening 100 years ago.

One spring Saturday a century ago, George Pierce Jr. decorated his prized 1909 Rambler in blue and gold trimmings and drove to the University Farm for a “basket picnic.”

The prominent Davis farmer and UC alumnus was joined there by an estimated 3,000 people who came from throughout Northern California for the dedication of the campus’s first dormitory.

That dorm would become North Hall, and the event would launch one of UC Davis’ oldest and biggest traditions — Picnic Day. In the 100 years since that first open house, the annual event has been canceled for only three reasons — a statewide hoof-and-mouth outbreak that led to the slaughter of close to 110,000 California farm animals and 22,000 deer in 1924; delayed construction of a gymnasium needed to house the festivities in 1938; and the campus’s closure in 1943–45 for World War II.

In memoriam

The 1909 picnic was organized by University Farm Superintendent Leroy Anderson to showcase the work of the campus, which then had just 18 regular students plus 10 from UC Berkeley and other places. In addition to the dorm dedication, activities included a number of speeches — one by Pierce, who had been a tireless advocate for a UC branch in Davis — live music and the “basket picnic,” an old term meaning bring your own food.

The event generated such interest, the Oakland Tribune reported, that local businesses closed and “special train service was secured to enable residents of Sacramento, Woodland, Red Bluff, Marysville, Oroville and other neighboring cities to visit Davis for the day.”

In 1912, students took over the organization of Picnic Day and have been hosting it ever since — adding, over the years, hundreds of exhibits and events, including a parade, the Doxie Derby dachshund races and Battle of the Bands. It has become one of the largest student-run events in the country. Last spring, Picnic Day set a new attendance record with an estimated 100,000 people. This year, Picnic Day is April 18.

No bull: Quiet Guys Finish First

(Megan Wyman/UC Davis)

When it comes to bison, a new study finds, the quieter bulls get the girls. “We were expecting to find that the bigger, stronger guys — the high-quality males — would have the loudest bellows, because they can handle the costs of it,” said Megan Wyman, a graduate student in geography at UC Davis. “But instead, we found the opposite. My collaborator in San Diego wanted me to call the paper ‘Speak softly and carry a big stick.’”

Wyman, Michael Mooring of Point Loma Nazarene University and a number of student interns spent two summers monitoring the behavior and recording the sounds of 325 wild bison in Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge in the Sandhills region of Nebraska. They found that the bulls with the quietest bellows mated more often and sired more calves. Listen to a recording of bison bellows.

Homing in on autism causes

UC Davis researchers have concluded that a dramatic rise of autism in California cannot be explained by changes in doctors’ diagnoses and is most likely due to exposure to chemicals or infectious microbes.

“It’s time to start looking for the environmental culprits responsible for the remarkable increase in the rate of autism in California,” said Irva Hertz-Picciotto, a professor of environmental and occupational health and epidemiology and a researcher with the UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute.

The incidence of autism by age 6 in California has increased seven- to eight-fold over the past three decades — from fewer than nine in 10,000 for children born in 1990 to more than 44 in 10,000 for children born in 2000.

Some have argued that this change could have been due to migration into California of families with autistic children, inclusion of children with milder forms of autism in the counting and earlier ages of diagnosis as consequences of improved surveillance or greater awareness.

However, an analysis of state health and U.S. census data by Hertz-Picciotto and Lora Delwiche of UC Davis’ Department of Public Health Sciences ruled out those explanations. They found that, among California-born children, less than one-tenth of the increased number of reported autism cases could be attributed to the inclusion of milder cases of autism. Only 24 percent of the increase could be attributed to earlier age at diagnosis. “These are fairly small percentages compared to the size of the increase that we’ve seen in the state,” Hertz-Picciotto said.

Hertz-Picciotto said researchers and policy makers should focus more attention and money on identifying environmental culprits. “Right now, about 10 to 20 times more research dollars are spent on studies of the genetic causes of autism than on environmental ones,” she said. “We need to even out the funding.”